How Not to Go Aground While Delivering Cargo in FOB Sales

When you do something on the daily basis, it feels like you know all ins and outs. FOB, CIF, CFR are the commonly used marketing terms and every trader is sure they know what stands behind the terms, but do they really? Could their confidence (or self-confidence) be detrimental to business?

What is FOB and what does it go with?

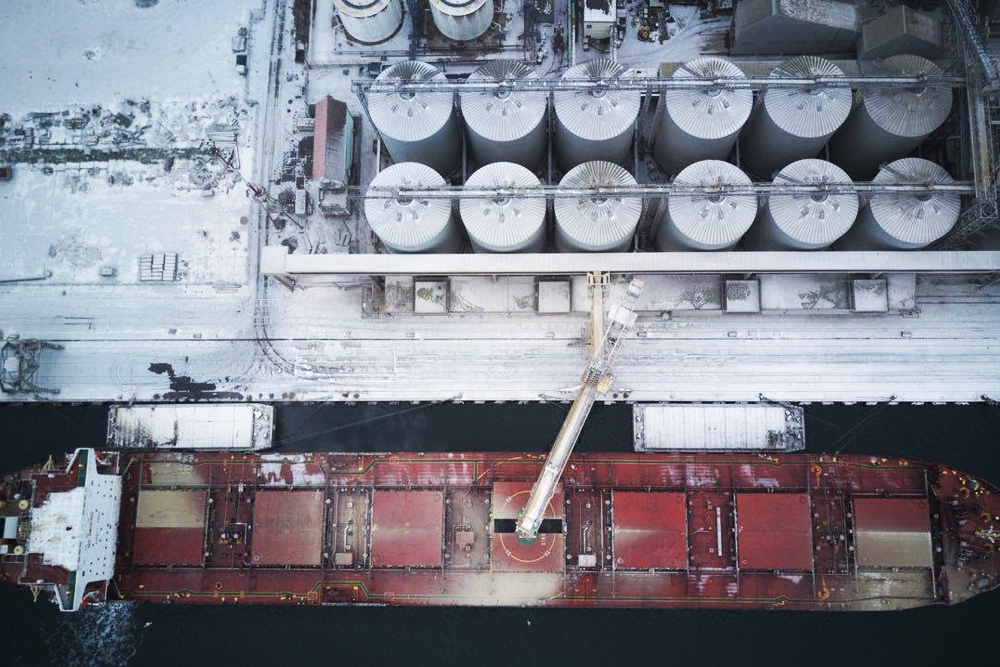

Let’s start at the very beginning. Today, the contracts under FOB terms are one of the most common ones on the market. FOB is, as it is well known, stands for “free on board”. The seller’s duty, under FOB terms, is to deliver cargo to a port and load it onboard a vessel. When the cargo is on board, further risks are transferred to the buyer.

Related story: A Short Intro into GAFTA/FOSFA Arbitrations (in Russian)

It seems we have just listed the basic principles every market participant knows inside out. However, experience shows that the details of the FOB contracts based on GAFTA/FOSFA arbitrations are shrouded in mystery. Let’s try to shed some light on them and bust popular myths about FOB contracts signed under the standard forms of GAFTA/FOSFA.

Myth 1. Any side of the contract may initiate the execution of the contract

Related story: Expiry Date of the FOSFA Arbitration: How Not to Lose Your Right to Trial (in Russian)

After the FOB contract is signed, it may seem that any side of the contract may initiate its execution. The reality is that the contract execution begins with the nomination of a vessel, which is the sole duty of the buyer. In a typical FOB contract, the time of the shipping is also up to the buyer. Therefore, it is the buyer who nominates the vessel and begins the execution of a contract. If the buyer does not fulfill this obligation in the due dates under the contract, things are bad (the contract is violated and the seller may seek compensation for the losses).

Myth 2. The seller has the right to start loading when it best suits them

Old hands in the business know that delivery time is a very fuzzy concept. In other words, it can be postponed or speeded up for months or weeks. The circumstances might differ. For instance, the seller has the goods and they wish to ship them as fast as possible (the sooner you ship the goods, the sooner the risks are transferred to the buyer). No matter how much the seller may wish to clear their conscience and their port terminals, they cannot ship the goods whenever it suits them, even when the timing is within the delivery period. Only the buyer decides when to nominate a vessel and deliver it to the port for loading, which means that it is the buyer who actually determines the start dates of the loading.

Myth 3. The goods need to be in stock by the beginning of the delivery period

If the first two myths could be easily debunked by common sense and the specificity of the agribusiness, the third one seems perfectly logical. If there is a contract with a determined delivery day, it is only natural that the seller needs to have the goods ready for shipment in the port by the delivery date. However, that is not always true. In fact, the seller does not necessarily need to have the goods ready for dispatch by the beginning of the delivery time.

A spoon is dear when lunch time is near: the seller needs to have the goods in the port by the vessel’s arrival. In other words, after the nomination of the vessel, the seller needs to start the delivery in such quantities that by the time of the vessel’s arrival, the cargo could be loaded without delays to avoid unnecessary expenditures for both parties.

Myth 4. Confirming availability of goods

Some market participants believe that the seller must confirm the availability of goods. Much to the regret of the buyer, that is a myth. The fact that the parties signed a FOB contract is not enough ground to make the seller compelled to do things not specified in the delivery terms. When signing a FOB contract one needs to take two things into account.

First of all, it is the nature of the business. With agribusiness, the goods may not be available yet when the contract is being signed (or when the delivery date is close). In FOB contracts, the seller is not obliged to confirm availability of the goods. Therefore, it is safe and even advisable to sign a contract without having the goods in ports. Otherwise, you may miss a lucrative deal. If the promise of making profit stamps out the fear of risks, there is the second thing to consider.

The second thing is the case when the seller must confirm the availability indeed. What is written down cannot be taken back – this is the rule that governs business. If the need to confirm availability is spelt out in the contract, the seller must do that. The time to repair the roof is when the sun is shining, so if you want to ensure certain obligations, spell them out in the contract.

Myth 5. Notice of readiness always means the vessel is ready for loading

One of the most important things in understanding the contract is its context. The notice of readiness does not always mean that the ship is ready for loading.

Related story: Agro-Cargo Is Blocked? No Need to Panic, There Is a Way Out!

The notice of readiness does indeed call for the company to make appropriate preparations for their cargo immediately. However, if the conditions for loading are not met (for instance, the holds are not cleaned after the previous voyage), the seller may dismiss the notice. Under such conditions, the loading window is nominated after the holds are cleaned up and the ship is approved for loading.

In legal terms, the buyer is obliged to deliver a vessel both materially and legally ready for loading certain goods in a certain place. When the vessel arrives at the port of destination, the buyer’s duty is fulfilled, now it is the seller’s duty to load the ship. According to the FOB contract, once the loading is complete, the risks are transferred to the buyer. Even if the goods are spoiled on board, that will be the buyer’s lookout.

Thus, the notice of readiness does not always mean that the ship is ready for loading. However, if the vessel is not physically ready for loading, the seller cannot reject the contract, they should wait for the vessel to be cleaned up and fulfill their contract obligations.

Myth 6. The goods must be loaded only during the delivery time

It goes without saying that the terms of the contract are the Bible of the deal, they cannot be neglected under any conditions. However, there are exceptions to rules, and it is better to know about the exceptions beforehand to avoid possible losses.

Let’s say, the last loading day is July 30. The chartered ship arrives on July 30. Technically speaking, the buyer fulfilled their obligation to deliver the ship in a certain period of time, but the loading may take more than a day. Nevertheless, loading the vessel beyond the agreed period will not be considered a violation of the contract under the given conditions due to the provisions of GAFTA/FOSFA which allow the loading beyond the agreed period. Thus, defaulting is not the best option for the sellers, if they want to avoid getting involved in an unwinnable arbitration process.

***

It is evident that even dutiful contractual performance under FOB terms may come to an unwitting breach of contract. Therefore, it is advisable to assess the potential risks ahead of time and specify them in the contract. However, if things go south, lawyers are always there to come to your aid.

Ivan Kasynyuk, Partner at the AVELLUM law firm