Nothing Personal: How China Replaced Almost All Agri-Imports From Ukraine

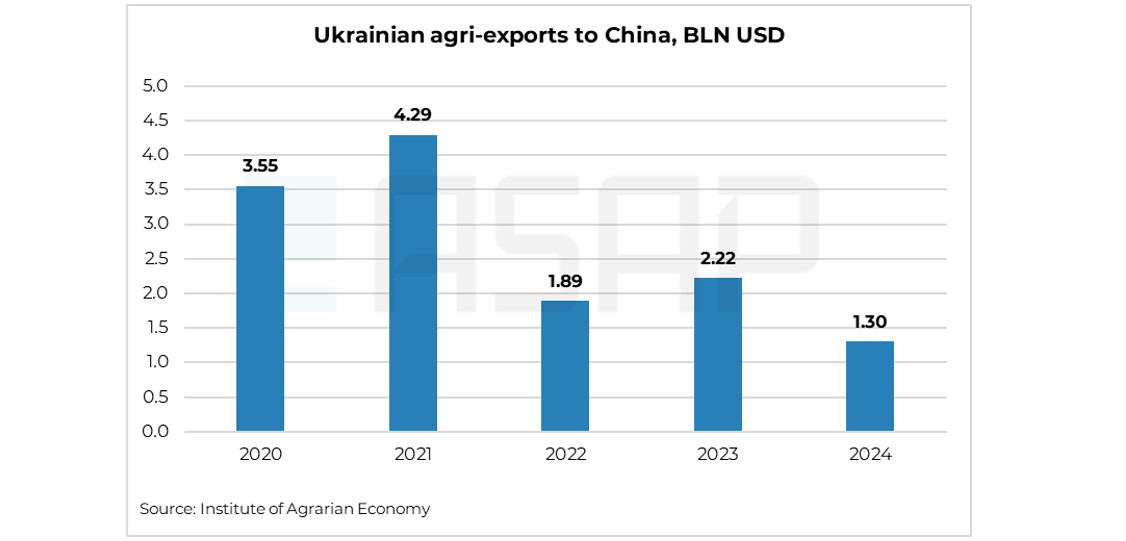

Just a few years ago, China was one of the biggest buyers of Ukrainian grains and sunflower oil. In 2021, Ukrainian agricultural exports to China hit a record 4.29 BLN USD. It seemed like a rock-solid foundation for long-term relations.

But 2022 brought a cold reality check: russia-Ukraine full-scale war, port blockades, skyrocketing risks. The result? Exports plunged nearly by half to 1.89 BLN USD. China didn’t wait — it swiftly turned to alternative suppliers.

2023 saw a slight rebound, but 2024 delivered another blow: China started scaling back agri-imports altogether. Last year, Ukrainian exports to China shrunk to just 1.3 BLN USD, one-third of the 2021 level.

Victoria Blazhko, Head of Editorial, Content, and Analytics at ASAP Agri, broke down these trade shifts and reached an undeniable conclusion: China is less and less seeing Ukraine as a strategic agricultural supplier. We were written out of the equation — no sentiment, just business. The market always favours those who pose less risk, offer more convenience, and provide a better price.

China cuts imports: nothing personal, just more domestic grain

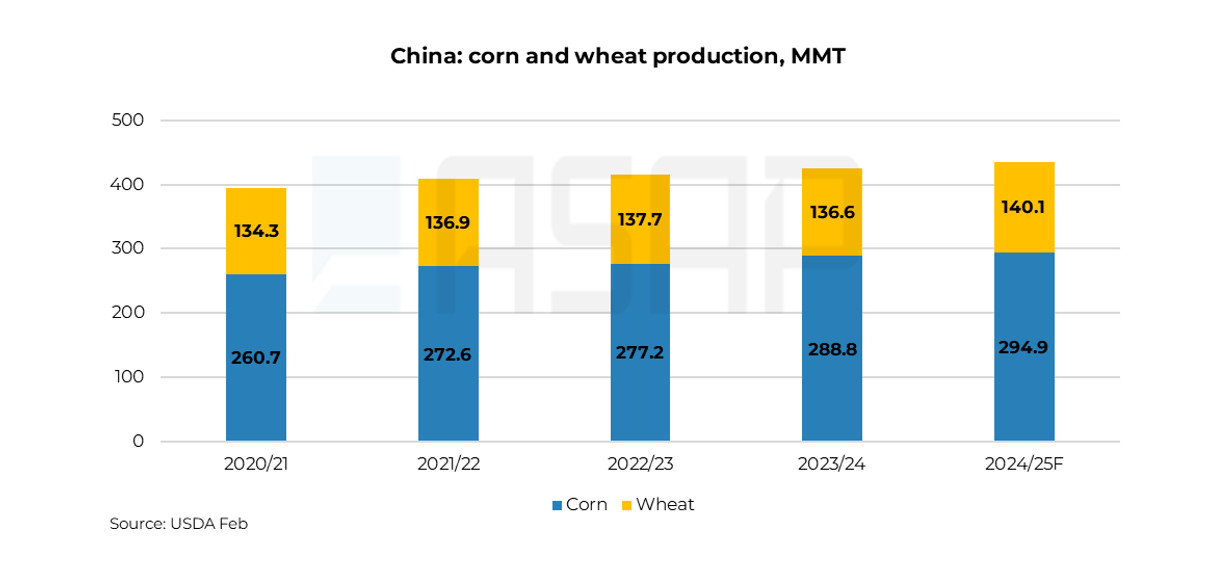

But before blaming China for "betraying" Ukrainian exporters, it’s worth looking at the bigger picture. The Chinese government didn't just switch to other suppliers — it ramped up domestic production to the point where imports are simply less necessary.

Over the past few years, Beijing has aggressively pushed its import substitution strategy, and 2024 marked a major victory. Total grain production surpassed 706 million tons, with corn and wheat alone hitting a record-breaking 435 MMT.

The logic is straightforward — and not exactly encouraging for Chinese suppliers: why import when you can grow it yourself?

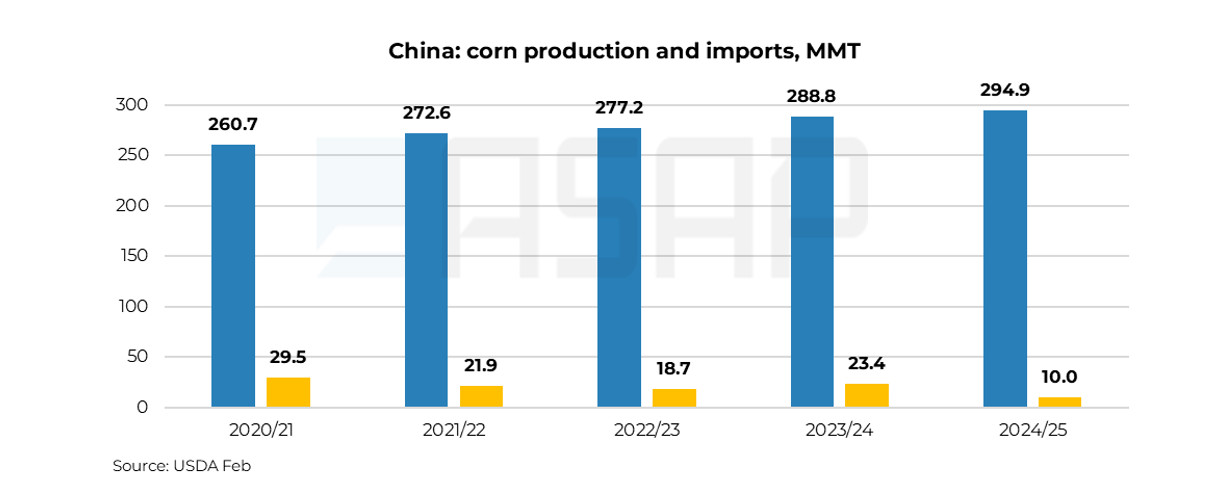

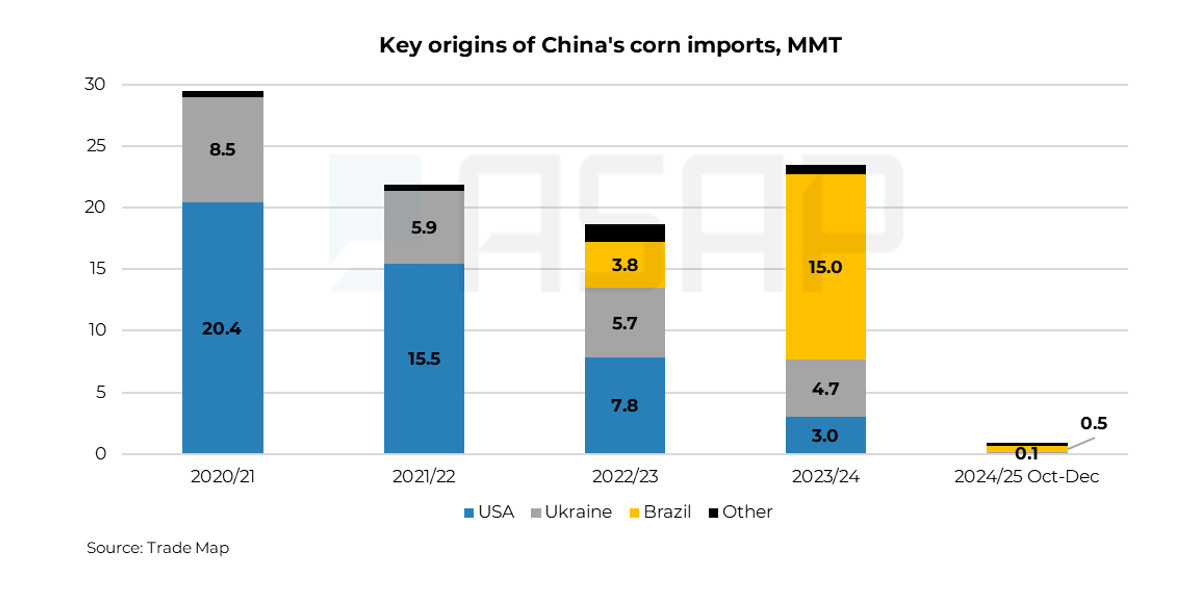

Let's look at corn, once Ukraine’s key export to China. China’s domestic corn production keeps climbing — from 260.7 MMT in 2020/21 MY to 294.9 MMT in 2024/25 MY. Meanwhile, corn imports are plummeting — from 29.5 MMT in 2020/21 MY to a projected 10 MMT in 2024/25 MY (USDA). And even that estimate might be optimistic—market whispers suggest figures as low as 6 MMT tons or less.

Does this mean China will completely stop importing corn? Unlikely. But the trend is clear: less room for imports, tougher competition. Especially when a heavyweight like Brazil is closing in.

Brazilian breakthrough: how China shifted its import priorities

In 2020/21 MY, Ukraine shipped a record 8.5 MMT of corn to China, second only to the U.S. (20.4 MMT). Then came 2022 — disrupted port logistics and shrinking exports to China. And the cherry on top? China opened its market to Brazilian corn.

That decision became a springboard for Brazil: in 2022/23 MY, Brazil supplied 3.8 MMT of corn to China. By 2023/24 MY, that number exploded to 15 MMT! Brazil is now China’s top supplier, pushing out both the U.S. and Ukraine.

This shattered a long-standing myth in the Ukrainian market. Many believed that China would always favour non-GMO corn, making Ukrainian grain irreplaceable. But reality proved otherwise — alternatives exist, and for China, the priorities are clear: price, availability, and logistics.

Barley: in China’s game of reconciliation, someone always loses

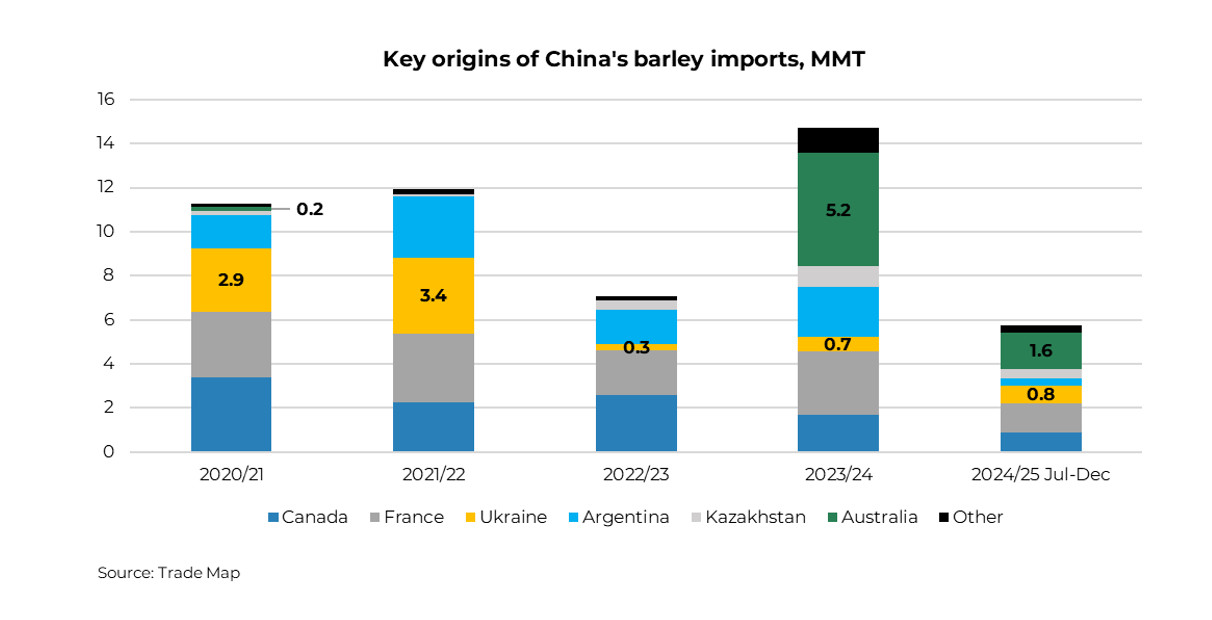

When it comes to trade, China is highly pragmatic in resolving disputes — especially when it works in its favour. The best example? The return of Australian barley to the Chinese market, which hit Ukrainian exporters hard.

Back in 2020, China slammed the door on Australia, imposing an 80.5% tariff on its barley. Officially, this was due to an anti-dumping investigation, but unofficially — it was political payback after Australia called for an inquiry into the origins of COVID-19.

Australian farmers panicked. China needed a new supplier. Enter Ukraine.

For Ukrainian exporters, this was a golden opportunity. In 2020/21 MY, barley exports to China tripled to 2.9 MMT. China became Ukraine’s biggest market, and in 2021/22 MY, exports increased further to 3.4 MMT.

But then, war happened. Ukraine’s exports to China collapsed below 1 MMT due to blocked ports. And in August 2023, China and Australia “suddenly” made up — tariffs were lifted, and Australian barley flooded back into Chinese ports.

The irony here? China once shut out Australia, handing Ukraine a surprise boost. Then, with its logistics in shambles, Ukraine ended up tossing the ball back.

As a result, in 2023/24 MY, Australia dominated the Chinese market, supplying 5.2 MMT of barley and pushing Ukraine to the sidelines.

Even though Ukraine has managed to ship 0.8 MMT so far this season, it’s a far cry from pre-war levels. And with China reducing its grain imports and a long line of alternative suppliers — Australia, Canada, France, Argentina, Kazakhstan — the road to recovery looks bleak.

Sunflower oil: once leaders, now outsiders

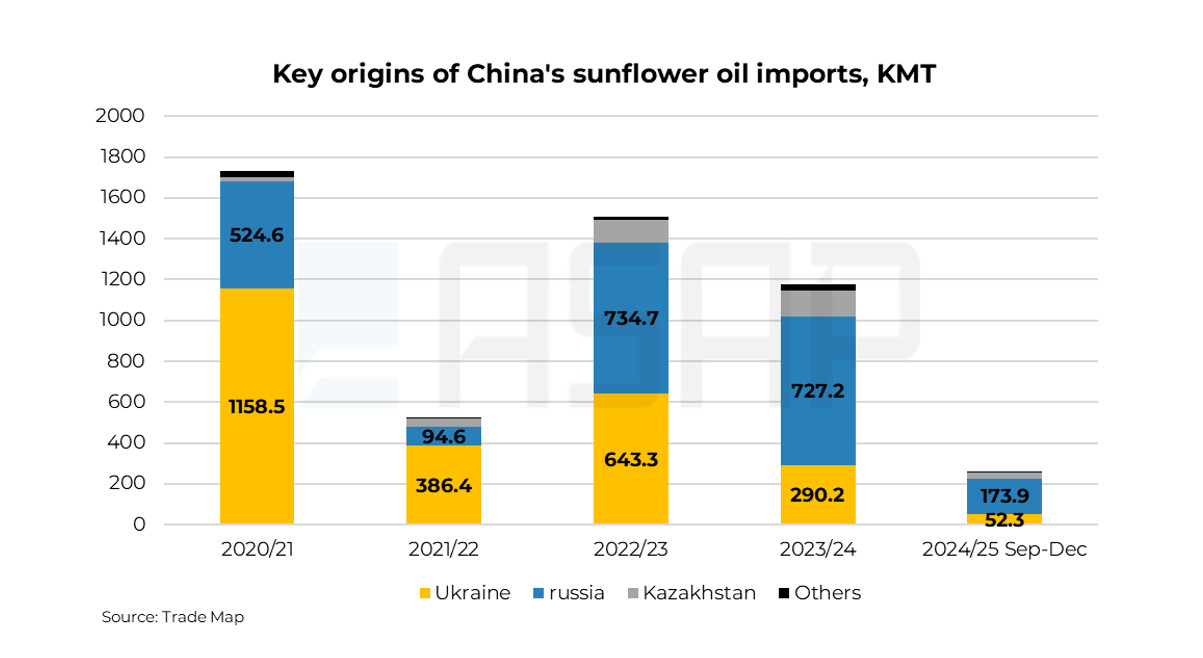

Once, Ukrainian sunflower oil dominated the Chinese market, with exports surpassing 1 MMT. More than 60% of China’s sunflower oil imports came from Ukraine.

Because of the war Ukraine’s market share plummeted to 25% and continues to shrink. In 2022/23 MY, Ukraine exported 643 KMT of sunflower oil to China. By 2023/24 MY, that figure had dropped to 290 KMT — more than a twofold decline. In the first four months of 2024/25 MY (September-December), exports barely reached 52 KMT.

Ukraine is no longer the market leader — new favourites have taken its place.

Who took Ukraine’s spot?

russia played every possible advantage: aggressive expansion, Ukraine’s crippled logistics, and ruthless price dumping. As a result, russia now controls over 60% of China’s sunflower oil market. In other words, nearly two-thirds of all bottles on Chinese shelves now bear a russian label.

Kazakhstan’s oil has also steadily expanded its presence in China. Over the past five years, its market share has grown from just 1% to 11% — quietly but effectively.

However, Ukraine’s biggest competitor isn’t just other countries — it’s alternative oils.

Palm oil is the undisputed champ of China’s imports, holding the edge for years thanks to its low price. Chinese buyers vote with their wallets — if there’s a cheaper option, other oils get left in the dust.

Soybean oil is another big player. China’s ramping up its own production, steadily cutting back on relying on imported vegetable oils altogether.

Sunflower meal: last bastion cracking

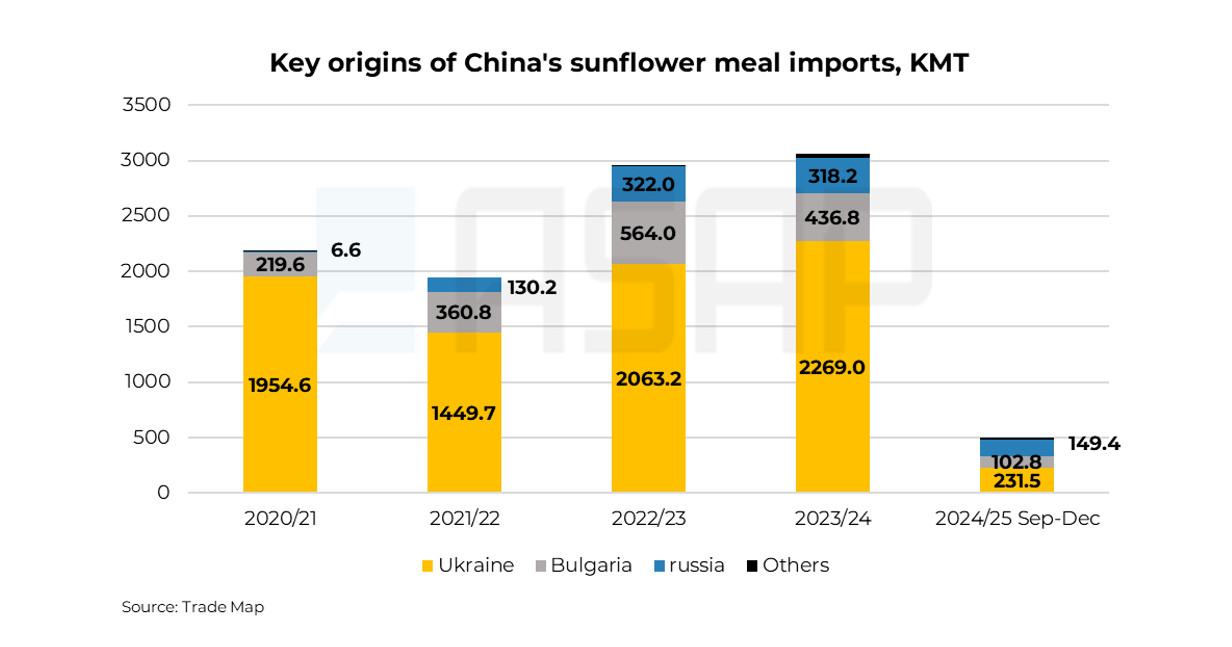

While corn, barley, and sunflower oil were losing the Chinese market, sunflower meal remained the last bastion. It is the only Ukrainian product whose exports not only didn’t decline but actually grew after the war began.

In 2022/23 MY, Ukraine shipped nearly 2.1 MMT of sunflower meal to China. In 2023/24 MY, exports increased to 2.3 MMT. But in 2024/25 MY (September-December), the numbers look downright alarming — just 232 KMT, nearly three times less than during the same period last year.

If we go back in time, Ukrainian sunflower meal secured its position in the Chinese market thanks to three key factors:

- The "state diet" shift. In 2021, the Chinese government took steps to cut its reliance on soybean meal, urging feed producers to reduce its share in livestock rations. Less soybean meal meant more space for alternatives — including sunflower meal.

- The budget-friendly alternative. In 2022/23 MY, soaring soybean meal prices led China to seek cheaper substitutes, and sunflower meal was a natural fit. While it contains less protein than soybean meal, cost-efficiency matters when feeding millions of livestock.

- The "many plates" strategy. China stopped relying on a single protein source. Sunflower meal comes from Ukraine and Bulgaria, rapeseed meal arrives from Canada, and this diversification provided China with greater flexibility and reduced supply risks.

What has changed this? Why has China suddenly pulled back?

- China is ramping up domestic soybean meal production. Large-scale soybean processing has ensured an ample domestic supply, reducing the need for alternative imports like sunflower meal.

- Soybean meal prices are falling. Previously, sunflower meal had a competitive edge as a cheaper alternative. But with soybean meal now more affordable, livestock producers are naturally opting for the higher-protein option.

- Ukraine's supply is tightening. Even if China wanted to maintain previous import levels, Ukraine simply doesn’t have the stockpiles it once did. Lower production means less availability for export.

The bottom line

The only thing that can bring Ukrainian products back to China is China’s rational economic interest. The formula is simple:

- Competitive pricing

- Stable logistics

- China’s actual need for imports

- Problems with alternative suppliers (if Ukraine’s lucky)

As the saying goes, it’s nothing personal — just business.

ASAP Agri will explore the outlook for Ukrainian grain exports in the 2025/26 season, including prospects for the Chinese market, at the International Grain Conference Grain Ukraine 2025, set to take place 29-20 May in Kyiv. If you want to be among the first to gain insights into key trends and challenges shaping the upcoming season — save the date!