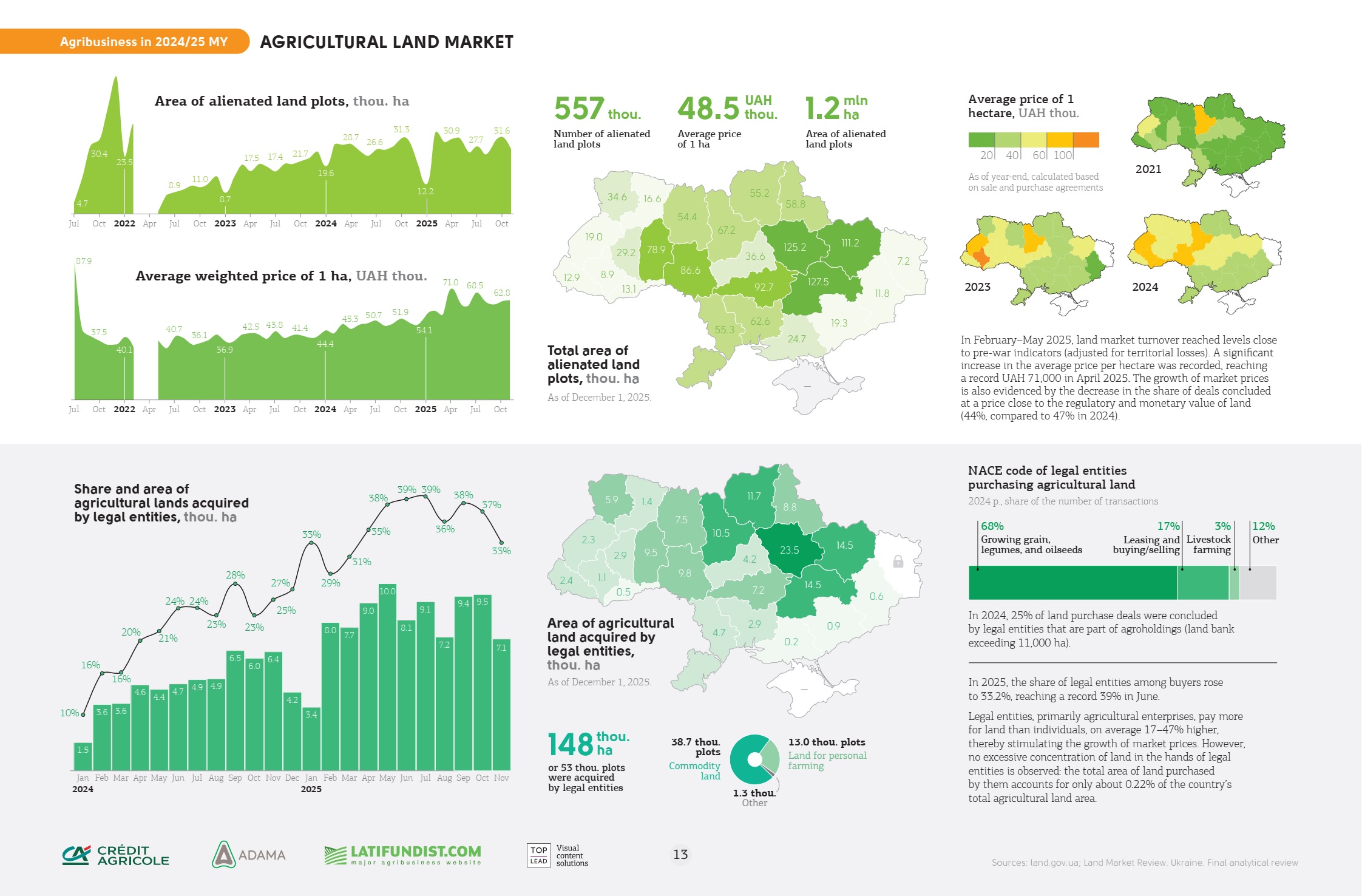

Ukraine’s Farmland Market: USD 1,500–6,000/ha and Declining Returns

Photo by: Latifundist.com

The buzz in Ukraine’s farmland market is not subsiding: investors are ready to buy several times more land than marketplaces can offer, and competition is pushing per-hectare prices upward. At the same time, land values are rising faster than rental income. As a result, investment returns are gradually declining.

How this market actually functions — and where official statistics diverge from real transactions — was explained by Volodymyr Nahornyi, co-founder of Volodar agency and project manager at agri-investment company Fortior Capital.

4% of the Land Bank Already Sold

According to Nahornyi’s estimates, about 4% of Ukraine’s total agricultural land bank has been sold to date. Annually, approximately 0.7–1% of land changes hands.

“This is a sign of a healthy market. If we compare it to real estate markets, 0.5–1.5% turnover indicates stability,” he explained.

Official Price Statistics “Limp”: Deals Tied to Normative Valuation

Another feature of the market is that the “visible” price does not always equal the real one. According to Nahornyi, a significant share of transactions is still formalized based on the normative monetary valuation (NMV).

“State analytics grow together with the NMV. But that is not always the amount the parties actually agree on,” he said.

As a result, official statistics reflect the figure stated in documents rather than the actual per-hectare price. As long as the market remains anchored to the NMV, the real price often exists separately — outside formal reporting.

He also notes that in most cases, sellers do not face high tax costs: they often sell their first plot (less frequently a second or third), which reduces the tax burden. Despite this, the market continues to “hide behind” the NMV framework, with the actual price existing in the informal part of agreements.

Real Prices: $1,500–5,000 per Hectare Depending on Region

According to Nahornyi’s observations, current transactions fall within a wide range:

- $1,500–1,700/ha — border districts of Sumy region

- $3,000–4,000/ha — Lviv region

- Up to $5,000/ha — individual deals in western regions

In western regions — Ternopil, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Lviv — the general price benchmark is higher, with sales often occurring at $3,000–5,000/ha.

The most active market zones, he noted, are Vinnytsia and Khmelnytskyi regions, as well as southern Kyiv region. Here, transactions around $4,000/ha have been recorded, with buyers typically being agricultural holdings or affiliated structures. However, this is more the exception than the rule and applies to roughly 10% of the market.

The Land Market and the War Factor

The war factor directly affects demand and pricing: the closer to the front line, the fewer willing buyers. Nahornyi cited the example of the Sumy region border area, where plots may cost $1,700/ha, while “across a forest belt” in neighbouring Poltava region sellers already ask $2,500/ha for similar soils.

In active combat zones or on mined land, demand can nearly disappear, and prices may drop to just a few hundred dollars per hectare.

Demand Exceeds Supply by 2–3 Times: Who Is Buying Land

Since the market opened on 1 July 2021, demand has consistently exceeded supply by two to three times, Nahornyi says.

“I often see investors willing to buy several times more land than all professional land platforms combined can offer,” he describes.

The expected “wave of IT professionals” did not materialize — they account for up to 10% among professional investors. The main buyers are:

- Tenant companies (small and medium — purchasing through the tenant legal entity; large — through beneficiary structures);

- Mid- and senior-level managers of agricultural companies;

- Other employees of agricultural enterprises;

- Entrepreneurs from related sectors (machinery, trading, agri-services).

Nahornyi concludes: those who invest are the ones who understand the asset best.

Returns Are Falling: Land Prices Rising Faster Than Rent

At the launch of the market, the ratio of rental income to purchase price provided annual returns of 7–10%. Today, returns are around 5% in hryvnia, Nahornyi notes.

“Rental payments cannot grow that fast and simply cannot keep up with land prices — yields are compressing,” he explains.

Previously, farmland competed with a “one-bedroom apartment near a metro station”: an apartment generated around 5% annually, while land offered about 7%. Now, the net cash flow has effectively converged with residential real estate.

The 15–30% figures advertised on platforms represent projected capitalization, not actual rental income, the expert adds. Land may appreciate by 10–15% per year, but this is not guaranteed: the market is overheated by demand, and a correction cannot be ruled out.

Investors Enter Through LLCs

A separate cohort consists of investors purchasing land via limited liability companies (LLCs). After the market opened to legal entities in January 2024, such players were initially rare, but by 2025, visible market participants had emerged.

Large companies structure acquisitions through multiple legal entities: each may hold several thousand hectares, sometimes up to 10,000 ha. The ultimate beneficiaries remain individuals. Similar structures with land banks of 100–300 ha across Ukraine are already widespread.

Tenants Have Not Lost Land En Masse — But Fear Remains

Before the market opened, there were concerns that tenants would be widely displaced following ownership changes. According to Nahornyi, such cases are isolated.

“Neither large holdings nor mid-sized farmers nor small operators are experiencing major confrontations or significant outflows of land banks,” he notes.

At the same time, fear encourages farmers to buy out plots preemptively. If competitors offer a landowner a higher price, the tenant often matches the market price to preserve field consolidation.

Leasehold Rights Nearly Catch Up with Ownership

The market for leasehold rights today is almost on par with the ownership market, Nahornyi says.

The difference between full ownership and leasehold rights with contracts of around seven years is approximately $500/ha. For example, in Vinnytsia region, ownership may be valued at about $3,000/ha, while leasehold rights are priced around $2,500/ha, excluding machinery and infrastructure.

In western regions, benchmarks are even higher: a farmer with a land bank of 100+ ha in a strong location rarely names a price below $3,000/ha for leasehold rights.

The typical contract length is 5–7 years, while 10-year agreements are rare and justify a higher valuation.

Land Appreciates, but Investment Yields Decline

According to Nahornyi’s estimates, farmland is appreciating by 10–15% annually in dollar terms. At the same time, investment returns are decreasing.

The reason is the imbalance between asset price growth and the ability to raise rental rates. Even despite higher lease rates in 2025–2026, rent does not keep pace with land price growth.

As a result, investment profitability declines: land prices rise faster than they generate cash flow.

ProZorro Heats Up the Market: Deals Up to $6,000/ha

In 2025, the number of private plots listed for land auctions via ProZorro increased, Nahornyi notes. This boosts seller proceeds and stimulates the market.

The market players cited cases in central Ukraine where auctions started at $4,000/ha and reached $6,000/ha, while in western regions, farmland was sold above typical regional benchmarks.

Nahornyi allows for speculative mechanics, where groups of participants may “push up” prices, after which the market uses these precedents as new reference points.

“We are still going to see many interesting features in this market,” he concluded.