Begin With Yourself. Michael Petrov on Machinery and Seed Producers He Refused to Work With Due to Their Presence In russia

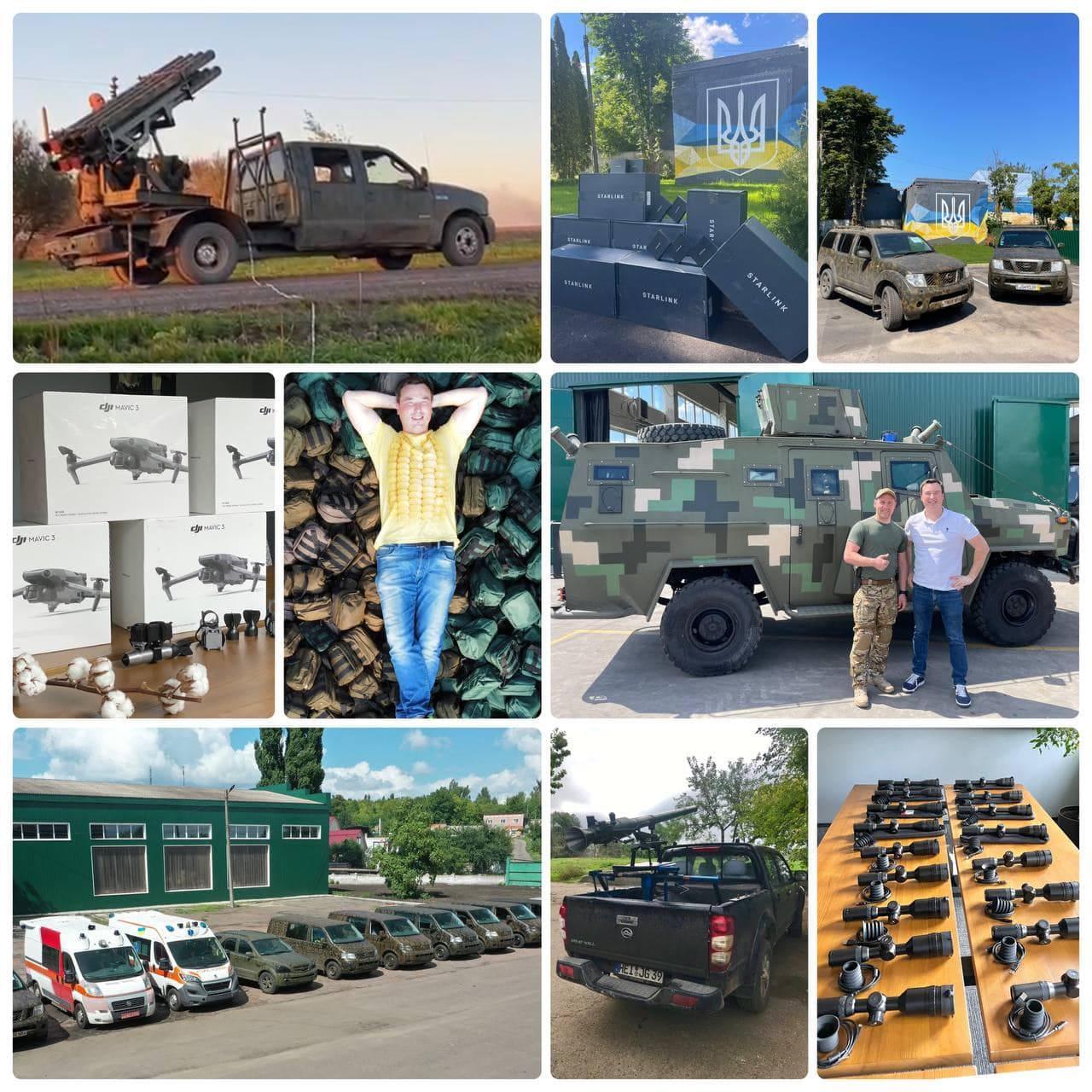

With the start of the full-scale invasion, Michael Petrov had to balance his position as Director of the Kernel Prydniprovskyi Cluster with his work at the Save Ukraine 2022 charity foundation he established. We wrote earlier about the functions of the foundation and how it helps the Armed Forces and the population. This time, we met to discuss a rather pressing issue for the Ukrainian agricultural market — the withdrawal of multinational companies from russia.

The Prydniprovskyi Cluster has already terminated cooperation with several seed and machinery producers that continue to do business in russia. "If we don't start with ourselves, what right do we have to demand that our partner countries — the US and the EU — do the same?" wonders Michael. During the conversation, he also explains why he is suing Jupiter 9 Agroservice, what kind of machinery the cluster is switching to, and whether it is possible to replace well-known seed brands with Ukrainian selection.

Latifundist.com: The Prydniprovskyi Cluster has been engaged in seed production for 8 years, hasn't it? Before the war, you invested a lot in irrigation. My point is that you have quite a long list of partners in this area. Who did you have to say goodbye to?

Michael Petrov: We do have a very extensive list of partners. Unfortunately, we no longer cooperate with the French company Lidea. The decisive trigger for me was when its russian office issued a congratulatory message on Fatherland Defender's Day. They didn't have to do that! It could have remained silent, as most "good russians" do. But no, it congratulates russian murderers on Defender of the Fatherland Day and continues to expand its share of the russian market as more conscientious companies leave. It even solemnly laid the first brick in the construction of a new plant on 24 February, when the first missiles flew into Ukraine. This proves that the company just wants to make money.

Latifundist.com: How much revenue did Lidea have from cooperation with the Prydniprovskyi Cluster?

Michael Petrov: Lidea received an annual income of about USD 1 million from our project. We grew Lidea seeds on commercial plots, which were then processed at the company's plant in Cherkasy region.

Latifundist.com: Was it a tough decision to break off the partnership?

Michael Petrov: I'd put it this way: it's a significant loss for Lidea, and a little for us. I am sure that another responsible company will quickly fill this niche.

When it comes to cutting ties with companies that have not withdrawn from russia, one has to start changing himself first, I believe. Otherwise, you simply have no moral right to demand that others do so.

Latifundist.com: You may be criticised for the fact that foreign seed companies have invested a lot in infrastructure development in Ukraine, which is jobs and taxes to the budget.

Michael Petrov: If they don't want to work in Ukraine, they can sell their plants. There will be buyers. Now, one of the tasks of a patriot is that if he or she is not defending the country in the Armed Forces, this person should make sure that it is abhorrent to cooperate with companies that have not withdrawn from russia.

Latifundist.com: But if we are talking about the Ukrainian offices of multinational companies, they often announce that they help the Armed Forces of Ukraine, IDPs(Internally displaced persons), and the local population. They say that the decision not to leave russia is the position of the parent company.

Michael Petrov: Ukrainian management is hostage to circumstances. Our task is to reach the headquarters. To make them understand that there is no option for further cooperation with russia. It is only there that we will be able to stir up the swamp.

Latifundist.com: Except for Lida, what other seed companies do you work with?

Michael Petrov: Monsanto, Corteva Agriscience, Syngenta, Limagrain, MAS Seeds and many others. Some of our suppliers are more decisive and quickly stopped paying taxes to the occupier's budget, but there are many who are waiting for a push, arguing that doing business in russia is for some humanitarian purpose. Therefore, the question of further cooperation with them is a matter of discussion with their management, especially their position and plans for working in the russian market.

Latifundist.com: Since we are talking about seeds, once at an event where the heads of procurement departments of agricultural holdings were attending, a representative of VNIS(The Ukrainian Scientific Institute of Plant Breeding (VNIS)) asked why they did not want to switch to Ukrainian selection and continued to cooperate with those companies still present in russia. Most were silent, looking away. Some of them said it bluntly: "Ukrainian selection has not reached that level." In your opinion, to what extent is this claim true?

Michael Petrov: It is not true when it comes to corn. Let me explain why. Many patents for the genetic code of corn either expire in the coming years or have already expired. For example, the genetic code for DK-315, which was popular 10 years ago, is already open. This means that any company can use it in its breeding activities, including Ukrainian companies. In general, genetics is a topic for another conversation. Because the developments that are now considered classic hybrids of multinational companies should have long been in the public domain.

I know VNIS hybrids well. Statistically, they perform no worse than the first-line hybrids of multinational companies. At least in my experience. That is why I am confident that our corn seed market will be "Ukrainised" in terms of production of parent lines, seed production and processing.

This business is quite marginal. There will be a demand for corn, at least if it is possible to export it from Ukraine. Our agricultural industry cannot survive without corn as one of the main crops for long, because there is a crop rotation system. No matter how much we would like to saturate it with oilseeds in difficult years, which is what we are seeing now, we still need a crop that can be sown for several years in a row. The land needs to rest from sunflower. Therefore, it will either be fallow or corn.

Latifundist.com: Well, what is the status of sunflower then?

Michael Petrov: The situation with the localisation of genetics is a bit more complicated. It is difficult to find hybrids of Ukrainian selection that are resistant to 7 races of broomrape (Orobanche) and resistant to different weather conditions. Plus, it's not clear whether Ukrainian breeding companies will be able to produce the volumes required.

Latifundist.com: Incidentally, did your cluster face a shortage of sunflower seeds this year?

Michael Petrov: Since we grow seeds ourselves, we have not had such a problem.

Latifundist.com: There are numerous great varieties of Ukrainian wheat on the market, but what about other crops, such as rapeseed?

Michael Petrov: There is also plenty of high-quality Ukrainian genetics for rapeseed, depending on the agro-climatic zones in which it is grown. There are some German and French companies that have good rapeseed genetics, but have not left russia.

Latifundist.com: Speaking of agricultural machinery manufacturers, which companies have you stopped working with because they have a russian connection?

Michael Petrov: Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, we have stopped working with Jupiter 9 Agroservice. This is one of the official John Deere dealers in Ukraine. The company is quite well developed in the north of Ukraine. Its owner is russian and has a russian business. They assured us that he was from Cyprus, sent us documents. But our position is that we will not work with those who do business in russia, pay taxes there, and thus sponsor the war against Ukraine. I even assume that the John Deere machinery that was stolen from agricultural enterprises in Zaporizhzhia, Kherson or Donetsk regions has been serviced by the russian dealer Jupiter 9 and is now working in russian fields. Service has to be done somehow after all. And where should it be done? At the dealer's.

Latifundist.com: From what I know, Jupiter 9 Agroservice is demanding that you fulfil the contract and pay a certain amount. Now you are in the courts. Market participants may get the impression that you have taken advantage of the situation and are simply trying to avoid fulfilling your obligations by saying "We do not work with companies owned by russians".

Michael Petrov: Yes, we are suing this company. We have already had two court hearings. It is demanding that we pay UAH 1.5 million in damages. You understand that this amount does not play a big role for us. It is a matter of principle.

With this case, I want to prove that I am not going to indulge those who are trying to sit on two chairs at the same time. I will also see how the judicial system works in Ukraine in relation to those companies that are under sanctions but continue to do business here.

The company's assets in Ukraine were seized in June last year, as stated by the Prosecutor General's Office. Yet, it keeps on working. We know that many agricultural companies in the region where it operates continue to have partnerships with it.

Latifundist.com: I wonder how John Deere's parent company feels about the fact that its equipment is sold in Ukraine by a dealer with a russian connection? After all, in March this year, it announced its complete withdrawal from russia and the sale of its business to a local private company.

Michael Petrov: We requested John Deere back in the summer of 2022. In particular, we asked whether Jupiter 9 Agroservice would remain its official dealer, given that the company's owner is russian. The company did not respond.

Latifundist.com: Both LEMKEN and Horsch have not scaled down in the russian market. Do you have any equipment from these companies and, if so, do you plan to give it up?

Michael Petrov: If we talk about the Horsch Maestro seeders of 2014, it was really a breakthrough. But now our company is completely switching to John Deere seeders, which are more productive than Horsch Maestro. And we will continue to move towards John Deere equipment to unify production. We also have CASE IH self-propelled sprayers, and equipment for tillage. Because unification is convenient and reliable. This is the factor enabling us to sow and apply pesticides on time.

Latifundist.com: A farmer will counter that it is a lot easier for a large agricultural holding to give up a Horsch seeder and a LEMKEN plough.

Michael Petrov: OK, then let's use this comparison as an example. There are two chocolates — Nestlé and Roshen. If it is possible to get the same quality, then I am surprised that Ukrainians do not buy Ukrainian products or from companies without a representative office in russia. For example, we have switched to sprinklers made by Variant Irrigation, a domestic manufacturer, and we are happy with the result. The price is lower, but the quality, as the practice has shown, is the same. So why overpay? And, working with this manufacturer, we know that our money is not used to benefit foreign investors but to develop a Ukrainian company.

Latifundist.com: Regarding other international companies reluctant to leave the russian market.

Michael Petrov: For starters, there is Corteva Agriculture, which exited the russian market right after the start of the full-scale invasion. This is because it is a company from the US, which is quite strict on sanctions. And then there is Syngenta, a Chinese state-owned consortium. This company continues to operate there because russia is a strategic partner for its country. I met with a top manager of Syngenta last summer. I asked her straightforwardly why the company was not leaving the russian market. She dodged the question. They are all diplomats. Everyone needs to save the starving population in Africa. And I'd say it's their call. How will it affect their business in Ukraine? This is what the Ukrainian client should be responsible for! Knowing the inside info, I can say that many Ukrainian producers of generic pesticides have almost doubled their production due to the decrease in sales of multinationals.

Someone from the market might argue that our business is heavily tied to some global companies and their unique products. But the choice of whether to continue cooperation with them and order the same volumes as before is a responsible decision for the head of the company.

Here's an example. There is a brand called Fuchs lubricants on the Ukrainian market of fuels and lubricants. After the full-scale invasion, the brand's management stated that it would not leave russia because the market was promising. Especially as giants such as Mobil and Shell have left the russian market. Now the company continues to actively sell lubricants to Ukraine, which are used to fuel engines and hydraulics of agricultural machinery. It turns out that due to the additional income in russia, it can afford to sell with a lower margin in Ukraine. Thanks to price dumping, it can cover more of the market and squeeze business from those companies in this sector that have left russia.

Latifundist.com: Michael, how does one then draw a red line for himself: which company to work with and which not? For example, if a company says that it is starting the process of exiting the market, should you work with it? Or not?

Michael Petrov: I am still in the process of defining this red line. But I will say that if each of us at least thinks about the fact that such a line can exist, that companies cannot operate and generate income in the aggressor and victim countries at the same time, it is already a good thing.

For example, in Ukraine, there is a French hypermarket chain called Auchan, which continues to operate in russia and even helps the russian occupiers. I don't understand what could make a Ukrainian go to this chain when there are other supermarkets around. There is a field of choice. If Auchan closes down because Ukrainian grocery companies do not want to work with this hypermarket, a new one will immediately take its place. Those employees who are unemployed will move to another employer and nothing will change for them. What will change is that their management will not make money here and finance russian aggression.

I would also love to see Ukrainian retailers labelling products from companies that are staying and expanding their business in russia. These are Johnson & Johnson, PepsiCo...

Latifundist.com: By the way, the case of PepsiCo is curious. The company continued to operate in russia while the russians were destroying its juice production and fruit and vegetable processing plant in Mykolaiv region.

Michael Petrov: Lots of such companies. There is another thing here: Ukrainians may know the name of a large company but not its brand. For example, Svitoch chocolate is now owned by Nestlé. The corporation claimed that it did not sponsor the war, but in fact, it is still selling most of its huge range of products in russia. Taxes paid in russia are equal to death coming to Ukraine.

Latifundist.com: Over the past seven years, Kernel has been pursuing managerial decentralisation. Does the company share your vision? Did it have a list of companies greenlit to maintain work with and those not to?

Michael Petrov: Decentralisation is what makes us successful. After all, each entity in the company can make its own management decisions and then be responsible for them. That is why I am sure that the company, which has already donated more than UAH 1 billion worth of aid to the Armed Forces of Ukraine, will echo my position: multinational companies should close their business in russia and not sponsor the aggressor. We have not received any lists from Kernel regulating our choice of companies to do business with.

Latifundist.com: What do other Ukrainian agriholdings stand on? Have you noticed them refusing to cooperate with companies that have not withdrawn from russia?

Michael Petrov: Multinational companies carrying on business in russia can provide deferred financing. That is why Ukrainian farmers and agricultural holdings do not refuse to cooperate with them. They have two choices during the war: either to close their business or to receive money for the goods in advance and somehow get through the season. For me, it is impossible to resolve this issue without government intervention. It should consider providing suppliers with special financing or offering factoring programmes from state-owned banks for postpaid contracts.

That's precisely why we are doing this interview — I want to make Ukrainians realize that the war with russia includes the economic front as well. After all, we cannot demand that our partner countries despise cooperation with russia unless we start doing so ourselves.

Kostiantyn Tkachenko, Natalia Rodak,Latifundist.com