Spain sees no extra appetite for Ukrainian corn without price edge — ASAP Agri

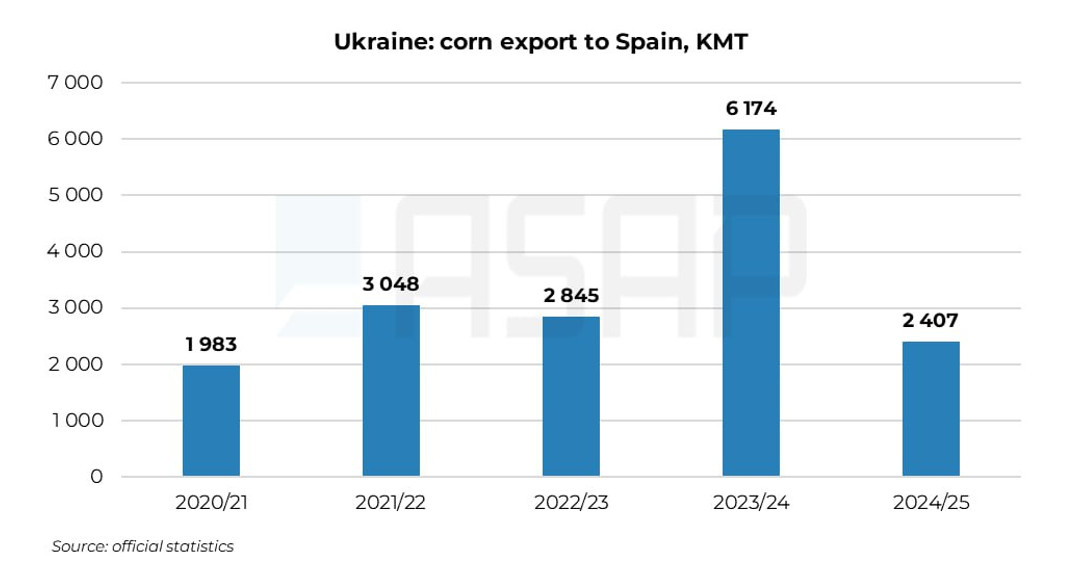

After losing China — once the largest buyer of Ukrainian corn — Ukraine is now facing another painful setback: Spain, historically one of its key EU markets. After peaking at over 6 MMT in 2023/24, Ukrainian corn exports to Spain have slumped to just 2.4 MMT in 2024/25 — barely a third of the previous season’s record. Volumes have essentially returned to their traditional range, but prospects suggest a possible further decline, notes Victoria Blazhko, Head of Editorial, Content and Analytics at ASAP Agri.

“The competition [for Ukrainian corn] comes from the U.S., which has managed to establish itself very well in the Spanish market — both in terms of price and quality,” says Jorge de Saja, General Director of the Spanish Feed Industry Federation (CESFAC), in a recent interview with ASAP Agri.

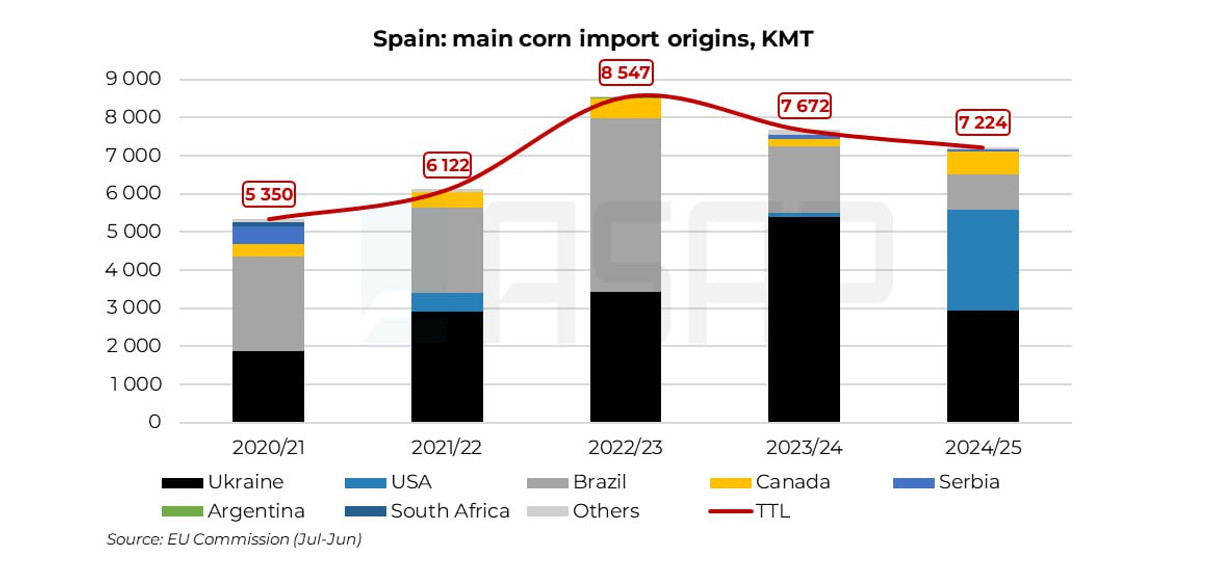

The shift is clearly visible in import data: U.S. corn flows into Spain have risen, moving from a marginal role to one of the top three origins. In 2020/21(July-June), Spain imported about 0.5 MMT of U.S. corn. After disappearing completely in 2022/23 and returning with just over 100 KMT in 2023/24, U.S. shipments surged in 2024/25 to 2.65 MMT — nearly matching Ukraine’s 2.93 MMT.

This marks the first season when the U.S. has challenged Ukraine head-to-head as Spain’s main supplier. Brazil, by contrast, has also seen its role collapse: from more than 4.5 MMT in 2022/23 to just 0.9 MMT in 2024/25.

In just one year, the U.S. has leapt from a footnote in Spain’s import mix to a structural competitor for Ukraine in one of its most important EU markets. And the momentum looks set to continue, with nearly half a million tonnes of U.S. corn already booked for Spain in 2025/26.

“At one point, we honestly thought we might lose the U.S. as a supplier because of the tariff discussions. We assumed we would end up importing less corn or importing it at a higher cost, which would have amounted to the same thing. That’s why we began looking again at Ukraine as a source. Now, with the tariff negotiations resolved — and resolved in fact at a very good point for the U.S. — I don’t think there is going to be much substitution,” says de Saja.

Two factors have defined the U.S. breakthrough in Spain: quality and, above all, price.

“In the recent past, we encountered some quality issues with Ukrainian corn. Nothing dramatic, nothing that created major problems, but still a fact. So, I don’t seea greater appetite for Ukrainian corn in the Spanish market unless there are clear price advantages compared with international competitors,” de Saja adds.

Last season, on a CIF Spain basis, U.S. corn was at times up to 20 USD/MT cheaper than Ukrainian offers, securing the competitive edge. And Ukrainian origin remains uncompetitive. As of 25 September, U.S. corn for October shipment was offered at around 242 USD/MT, close to Brazilian levels at 239 USD/MT, while Argentina was quoted the lowest at 229 USD/MT (though Argentinian supply is currently excluded from Spain due to pesticide restrictions). Ukrainian offers remained the highest at 251 USD/MT for handy-size shipments for October and 246 USD/MT for November shipment. This price gap leaves Ukraine disadvantaged not only against the U.S., but also versus Brazil.

Another factor weighing on demand is Spain’s own crop. According to the European Commission, Spain is expected to harvest 3.52 MMT of corn in 2025, up from 3.32 MMT in 2024. As de Saja points out, this means Spain’s “domestic needs will naturally be somewhat reduced” this season.

Ukraine has only just begun harvesting its 2025 crop, and the slow pace so far is helping to support prices. Yet once new volumes start flooding the market, pressure on prices is set to intensify — particularly amid uncertain demand prospects in Europe, with Spain at the forefront. Without a clear price edge, Ukraine risks losing even more ground among Spain’s main suppliers and may be forced to seek alternative outlets in a highly competitive global market, where buyers willing to pay a premium will be hard to find.