Analysis of the Global PPP Market

The global market for plant protection products continues its growth by 3-4% annually. The recent M&A activities the world's largest manufacturers are involved in will not affect the cost of agrochemicals for farmers. National producers of PPPs have no reason to worry in the face of mergers and acquisitions creating bigger companies.

Today public initiatives on the prohibition of certain active substances are actively taking place. This is a cause for concern not only for manufacturers but for the entire agricultural economy. The move from science and scientific decision making into emotions and politics playing a role in the decision-making process is not good for any country, any economy. It becomes a bit difficult for companies to operate. And this is a bigger problem in Europe. When politics becomes an important part of the decision-making process, it becomes a difficult place for the industry to operate, which will eventfully relocate to another place in the world, where it’s easier for to function. So that’s a loss for any political system or economy that doesn’t go for science base in a decision-making process.

Glyphosate has received restricted approval in Europe and many member states are asking for a ban on it. In Europe, the producer's influence is almost zero. According to EU rules, if a molecule or an active ingredient such as glyphosate is renewed, it’s supposed to be renewed for 15 years. But because of all the political pressure from certain member states, the renewal was only set for 5 years. This breaks the policy the European Union set up.

There are some member states, for instance, France, that are politically opposed to glyphosate. The French President Macron recently announced that he wanted glyphosate out of the country within 3 years. But then, when it was added to the bill in the Parliament, it was rejected. So, it’s basically one party against the other, one member state against the other, it’s politics rather than a really clear scientific decision-making process. That is what regulations are all about — they should be rational, not emotional.

Ironically, glyphosate is considered to be one of the safest pesticides. It has been in use for almost 40 years already. Glyphosate initially came to the market in the mid-70s. So, there are plenty of generic manufacturers also producing glyphosate, thus the price has definitely gone down. But it really is a very effective product. After spraying glyphosate, a farmer does not need to apply more herbicides in the field.

Glyphosate is basically a non-selective herbicide. That means if you spray it on the field, it will kill all the plants. But in a genetically modified (GM) crop, it doesn’t get killed. But if glyphosate comes out of the equation, you will have to use herbicides before the actual planting of crops in order to kill weeds. That will result in excessive use of the herbicide, even before the sowing has taken place, and then once the crops are coming up on the field, you would have to use a number of selective herbicides to kill specific weeds in the field. Instead of 1 or 2 applications of glyphosate, you will actually have to do 5 or 6 applications. It raises costs, it’s not good for farmers economically, and it’s not good for the environment. These things are obvious and it is strange to see much opposition in this matter.

The market gets affected simply because we have to use more products. Moreover, there is no alternative to glyphosate in the market, there’s no other non-selective herbicide that can tackle weed in the way glyphosate does. So the alternative is to do more sprayings before and after the planting. It is not the right way forward for farming when everyone is talking about sustainable agriculture. Suddenly we find ourselves in the situation, where we will have to actually increase pesticide usage 2 or 3 times.

Legal precedent

The Monsanto case was driven more by emotions rather than by rational lawmaking. I don’t think any company can be seen as liable if regulators of that country have declared the certain product as safe. Monsanto somehow became the symbol of all the negative propaganda that is being going on for many years around the world.

When the jury awarded USD 290 million to this person a couple of months ago, Monsanto appealed the decision and the amount was reduced to USD 80 million. But the thing is that Monsanto, which is now Bayer, remains guilty all the same. This is not good for the industry. If the national rules are not seen as the final, how does a company decide on what product it would get into the market? It might have a negative impact on all companies.

People who know nothing about science and agriculture, suddenly have an opinion on what should and should not be used. For instance, the latest news on Agrow was that there is an environmentalist group in the US, that has set its own standards on how much glyphosate should be allowed in a product. The US EPA has a certain standard, but this group thinks that the EPA doesn’t know what it is doing. It set its own standard and it’s now pressing the companies to follow its standard, which is ridiculous.

Generics vs originators

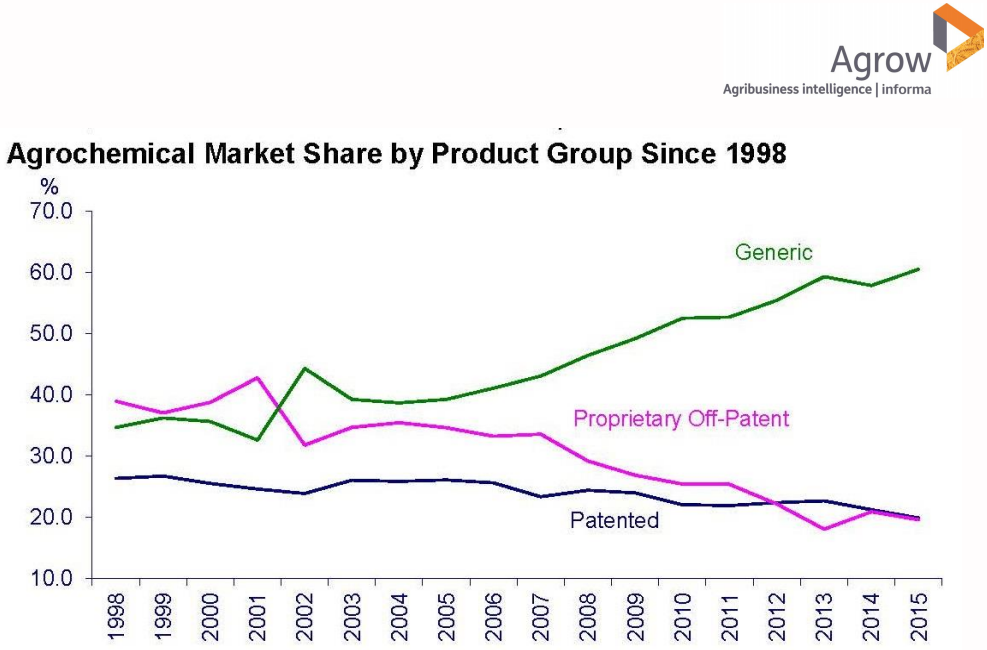

It’s not the case that genetics are completely conquering the market or overtaking it, but it is a fact that a share of generic products in the total output of pesticides has been increasing over the years. If you compare with the year 2000, patented products accounted for some 25% of the market, but currently they come for at least 20%. And there is a category called off-patent pesticides, which technically are generic in the sense that they do not have patent production. But in “off patent products”, the leading company still retains an over 90% market share.

So patented and off-patent products account for some 40% on the market and generic products account for 60% of the global market. But if we look at the genetics part of the market, more than half of it is taken by 5 or 6 R&D based companies. The global share of these R&D based companies is 65 to 75% of the global market and it’s only to a remaining 25-35% that is being taken by the smaller and the medium companies.

M&A impact

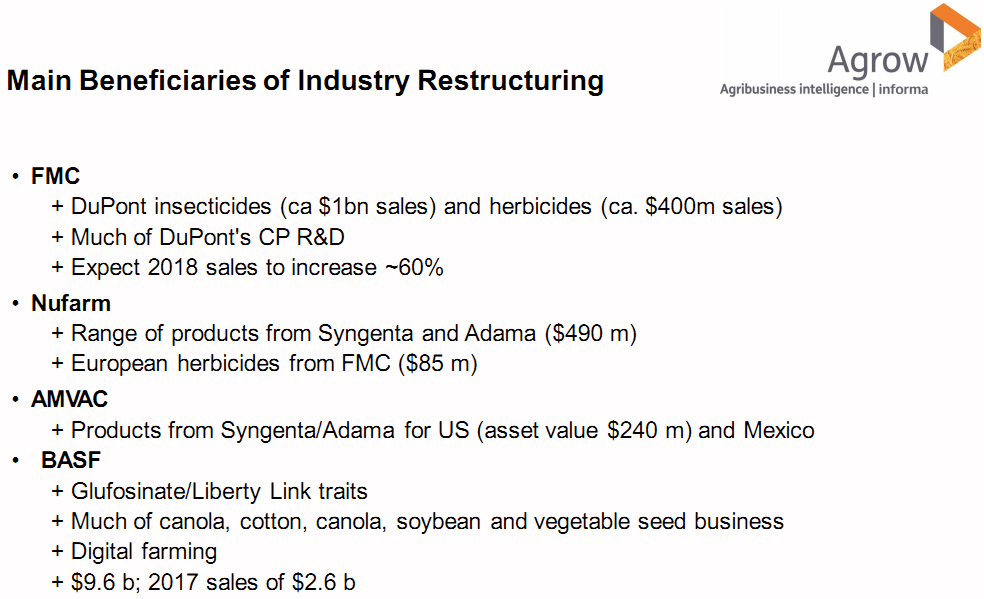

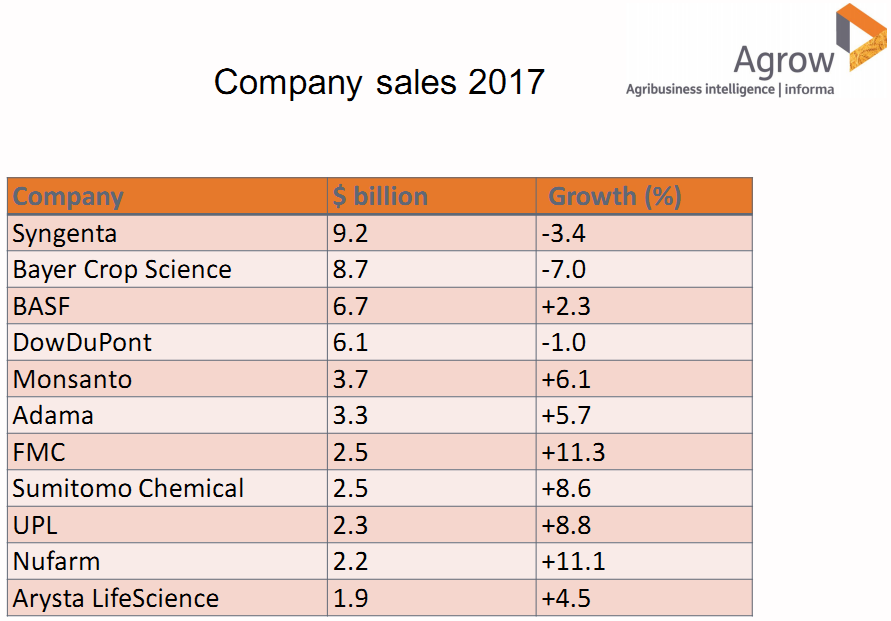

In the last 2-3 years, we have seen 3 major M&As in the industry. First it was ChemChina that acquired Syngenta, then Dow and DuPont got together and finally, Bayer has acquired Monsanto. There was some concern because of consolidation in the industry. It was felt that these companies would have too much power, become too big and then they would be able to control the prices. But when these companies got together, they had to sell off a large part of their combined business, because there were requirements from competition authorities. For instance, DuPont had to sell off its entire insecticide division, which represented its biggest selling products. It had to sell off a lot of herbicides, which were taken away by FMC. So FMC in the next 2-3 years will double its size.

Thus, the number of big companies still remains the same, and the size of the bigger companies will still be proportional. It will not impact the prices.

The idea behind the integration and coming together of the companies was that, first of all, the market has been in a difficult situation in the last 2-3 years. It has been in a state of decline due to a number of factors, like currencies fluctuations, political instability in Latin America etc. But once the companies get together, they are able to subsidize on research, production costs and bring competencies together. For instance, Bayer is clearly the leader in agrochemicals, Monsanto has an expertise in biotechnology. And now when these two strengths come together, it’ll be easier to develop new technologies.

I don’t think that the consolidation is the global market will have impact on the local manufacturers. GM crops are not permitted to be cultivated in Ukraine and most of the EU member states. So it doesn’t impact the Ukrainian market at all when it comes to agrochemicals. In the PPP market, Bayer’s size is more or less similar because although it has acquired glyphosate along with Monsanto, it has had to sell its glufosinate and its herbicide pipeline to BASF. So the equations have not changed and for any local producer, which has been on the market for some time. There is no cause for concern.

Biological products

Biological products are seen as a move towards the future of crop protection. Most of the bigger companies started looking at them 3-4 years ago when they were facing a lot of public pressure. But the thing is all the big companies have a sizable presence in biopesticides as well. This is in fact the fastest growing sector of the crop protection market.

If you compare biopesticides with chemical ones, the latter have been declining for the last 2-3 years. But if we analyze a longer period, we will see that the market is increasing by around 2-3% globally, whereas biologicals are growing at a rate of 15-20% annually, and yet they hold a tiny part of the chemical industry. The global market for agrochemicals is just under USD 60 billion, it’s around USD 57-58 billion for agrochemicals and biologicals should not account for more than 3-4%. Now it’s a small segment, but it’s going to increase in the next 5-6 years to a 5-6% share. Biological products are increasingly often used in combination with chemical products. So there’s a misunderstanding that biologicals are only for the organic sector.

Resistance manifestation

Resistance develops to a molecule, when there’s overuse of a particular molecule to control a particular pest and when that molecule is not combined with other kinds of chemistries. That is how pests start developing resistance. Ideally, you should have 2-3 different type of chemistries to control a pest, so that when different chemicals are applied, the pest cannot have a resistance to a specific one.

I will take the example of neonicotinoid insecticides here. As they have been mostly banned in the EU, farmers are using more of synthetic pyrethroids for pest control. The concern for the industry is that within the next 3-4 years, the pests will become so resistant to pyrethroids, that then you’ll have to come up with a new tool. It’s very difficult for the companies to come up with the new molecule, because it’s a very long process. Typically it takes around 10 years for a company to start researching a molecule and finally getting it into the market. There are so many trials, so many experiments to be done and the entire process takes something like USD 250-280 million.

Companies are getting more hesitant in bringing on new products, because when they do, you never know when a court case might come up against some product at some level and all the investment goes out. The companies are definitely working on new products, but the amount of funding, that is going into chemistry is now getting less and it is more towards biotechnology.

More problems with resistance will arise, if products are randomly taken out of the market without looking at what impact they may have. For instance, I go back to France again: they have recently banned 5 neonicotinoids, whereas the EU has banned 3 of them. France wanted to prove something, so it banned 5 instead of 3. And apart from that they also declared that 2 new products — one from DowDuPont and one from Bayer, are also intended to be banned in the next two years. These are completely new product chemistries, which would have been great for the farming community and much better in resistance management.

Reasons for optimism

The market had been growing very steadily since the year 2008. And a lot of that growth had been coming either from Latin America or Eastern Europe. But in 2014, there was a combination of a number of factors. Falling commodity prices made farmers seek ways of production cost reduction. Apart from that, there was a lot of political instability in Latin America. There was also poor weather for a couple of years mainly because of the El Nino weather phenomenon. The weather impact was felt especially in regions such as part of North America, Latin America, even in Asia in India and Australia also had an impact.

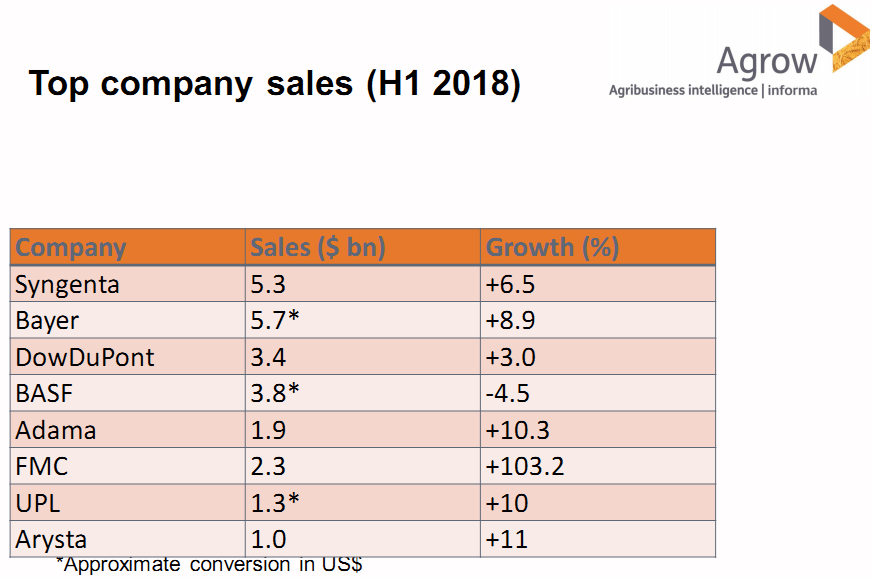

The combination of all these factors led to an 11-12% declining market for two consecutive years (2015-2016). But now, starting from 2018, projections indicate that the market is getting back into a growth mode again. For the first half of this year, most of these companies have recorded sales rises between 5% to 15%. FMC has doubled its sales in the first nine months of 2018.

It is a good time for the industry. But one of the problems in Brazil was that there was a glut of inventory and pesticides in the distribution chain simply because a lot of companies had pushed too much product into the market. Because of that, local distributors had stopped purchasing products, which then led to decline in the market. Now that glut has been reduced and business is functioning as normal. Projections are the market will increase by 3-4% this year and this will be the case for the next 3-5 years.

Future farming

Vertical farms, precision farming, artificial food — all these areas are promising. Everyone talks about the population increasing and that means you’ll have to have more productivity. For more productivity, you need to have better crop protection products and better agriculture. In case you don’t have the best tools available, the only option is to increase the amount of area you can cultivate. That means cutting off forests, which is not a good option from the environmental point of view. Another option is vertical farming: you start farming in the areas that are traditionally not used for farming — you start farming in cities. That can possibly open a bit more land for production of regular crops.

Apart from that, digital agriculture definitely is a step into the future. All big companies are investing a lot in it. That was one of the reasons Bayer took Monsanto, because Monsanto was one of the early entrants in this field. It has already made a good progress in digital agriculture and integrated farming. The idea is that farmers increasingly will have use of precision agriculture tools and thus reduce their costs and environmental impact.

Related story: Agriculture "In Vitro": How to Grow Meat, Milk and Eggs in a Laboratory

As for artificial food, there’s a fact that more people are eating meat rather that giving it up. We will have a need for more and more meat production in the future. That would mean more feed stuff going towards the animals and increasing global greenhouse emissions. Or the other option is growing food within labs. The only thing is for people to get over the initial inhibitions, when they are scared of new technology. The more people will understand, the easier it will be to accept these technologies into regular life and that is the way for the future. It’s only a matter of time before they become a part of regular life.

Sanjiv Rana, Editor-in-Chief of Agrow