Iva Rove Ukraine (Inc.): How the War Turned an Importer of American Fertilisers into the Creator of the Largest Consortium of Humanitarian Aid Producers

Photo by: Iva Rove Україна (Inc.) / Iva Rove Ukraine (Inc.)

Just a year ago, Iva Rove Ukraine (Inc.) specialised in supplying Ukrainian farmers with nitrogen stabilisers and anhydrous ammonia application equipment. Today, it is the coordinator of the largest consortium of food producers in Ukraine, RIDNE, which, in cooperation with such international foundations as the Global Empowerment Mission in partnership with The Howard G. Buffett Foundation, Health Right Int., Mission Eurasia, Human Bridge, Vinden, THK Norway, Ö-hjälpen and others provide the country with humanitarian food kits.

We talked to Serhiy Kovalchuk, Commercial Director of Iva Rove in Ukraine, about how the company managed to become a leader in a completely new market segment in such a short time, and what is more important — charity or business.

It all started with wheat

Latifundist.com: How many years has Iva Rove Inc. been operating in Ukraine?

Serhiy Kovalchuk: Iva Rove Inc. has been operating in the Ukrainian market for 10 years. Initially, we specialised in supplying American humates to Ukraine. Over the past three years, we have focused on sales, anhydrous ammonia application and nitrification inhibitors for nitrogen fertilisers. All these are unique developments of Iva Rove Inc. and Koch Agronomic Service. In addition, we supplied American cultivators and equipment for the application of anhydrous ammonia and inhibitors. In other words, we offered comprehensive innovative technological solutions.

Latifundist.com: Nevertheless, the war has changed everything. Has it affected your company?

Serhiy Kovalchuk: Of course, it has. Although, in fact, this is a complex and ambiguous issue. On the one hand, the potential demand for nitrogen inhibitors has only increased since the war started, as the availability of nitrogen fertilisers, such as UAN, has significantly decreased on the market, not to mention the price, which has increased by 30%.

At the same time, most farmers faced a shortage of working capital, which made it difficult to make standard calculations. That's why we came up with the idea to return to barter schemes — to exchange our fertilisers for grain.

We have a partner, the Bila Tserkva Agricultural Group. We have been cooperating with them fruitfully for a long time, we even travelled to the US together to attend international exhibitions. We offered to pay them in grain. Besides, it was the sowing season, the time to apply inhibitors. We started with wheat.

Latifundist.com: You got the wheat. What's next?

Serhiy Kovalchuk: The fact is that we are co-owners of the Buky Food Product Plant. This is an ordinary rural factory located in Cherkasy region, in the village of Buky. Officially, its main activity was the production of soft drinks and mineral water, although it can also produce oil, pasta and cereals.

Before the war, it hardly worked at all — a classic post-Soviet enterprise. So, we organised processing at its premises. We had the technical capabilities to do so. In particular, we had a relatively new mill and a small oil-pressing shop. We cleaned them, restored them and reopened production: we brought in wheat and started processing it into flour, and flour into pasta. Simultaneously, we launched vegoil production.

Latifundist.com: But production is worthless without established sales.

Serhiy Kovalchuk: Exactly. The question arose as to what we should do with our food kit. In March-April 2022, the agricultural market was in complete turmoil — no one knew where to go or with whom to work. But even then, it was clear that humanitarian food aid would be one of the most important areas for Ukraine for a long time to come.

We analysed the situation and rather quickly reached an agreement on cooperation with international humanitarian funds. Our American contacts helped us a lot with this. They recommended us saying that there is a Ukrainian company to cooperate with. Such references played a very important role at the initial stage of our development.

The success of fine vegetable oil. And more

Latifundist.com: What exactly did you offer your international partners?

Serhiy Kovalchuk: We formed the first food kits from the three items I mentioned — flour, pasta and oil. We started working with one American and two Scandinavian foundations with these minimum sets. Almost immediately, in March 2022. Everything is done under direct contracts.

It was basically a classic tolling scheme. The foundations gave us money and told us where to deliver the ready-made food kits. But most of the foundations asked us to bring them to their warehouses. For example, some in Sumy region, some in Kharkiv region, etc. And it turned out that the model works.

Latifundist.com: What vegoil did you put in the kits, the one from the crushing shop?

Serhiy Kovalchuk: Yes, with ordinary village vegoil, unrefined and fragrant. And our foreign partners accepted this format of cooperation. They liked it. They saw that we can do it. And they said: "Can you also make cereals, peas, and so on for us?". Of course, we agreed. And we began to involve our partners in the business. In particular, the Grocery Factory. This is the Zhmenka brand and our old friends. They have a cereal factory in Kyiv region, in Skvyra, which is relatively close to ours.

This enabled us to expand our product range to six items, including barley and wheat from our farm partners to be processed into cereals. Our foreign partners say: "That's great! Can you expand further?". We cooperated with other producers and grew — today our humanitarian food kits already consist of 18 different products.

Nothing can be dearer than that

Latifundist.com: ...And eventually you established the brand Ridne.

Serhiy Kovalchuk: The idea to brand our products came up at once. The message was simple: if production volumes are growing and there are prospects, why not register your own trademark? That's how TM Ridne was born.

At first, we launched the production of pasta, sunflower oil and flour under this brand. Then we added cereals. And now we pack a wide variety of products under the Ridne brand, including sugar, condensed milk, sardines, canned meat, chicken and even rabbit.

We also produce Ridne herbal tea. The largest production of medicinal herbs in Ukraine is based in Poltava region, on the border with Dnipropetrovsk region. The company mainly exports them to Israel, the USA, and Germany. But we came to an agreement, again on barter terms: we supply the company with our agrochemical products, and they supply us with herbal tea, which is an auxiliary product for them. It's perfect cooperation.

Latifundist.com: Is the production volume high?

Serhiy Kovalchuk: Quite large. In general, the humanitarian consortium produces about 2,000 tons of products per month on average. That is, all kinds of products. We are currently using 10,000 packs of herbal tea alone for food kits. And this is despite the fact that tea is generally not a popular item, and we include it only in separate humanitarian food sets.

We expanded our processing capacity almost immediately. Last April, we acquired another village plant in Cherkasy region, in Ivanky. We structured the production. In Buky, we produce pasta, sunflower oil and flour. And in Ivanky, we produce various cereals. In addition, we have a fairly powerful packaging line here, we bought it in wartime. We pack sugar, cereals, pasta and peas.

Obviously, our partners help us: from small farmers and producers to large holdings. For small partner farmers (100-300 hectares), having a constant supply of grain to our plants is a real lifesaver, as it gives them predictability in production. Farmers have even made their cropping plan based on our grain needs for processing. For example, we are following this plan for peas, wheat, barley and buckwheat.

Where does cooperation with GEM start?

Latifundist.com: But your head office is in Poltava.

Serhiy Kovalchuk: Actually, the location of the office is a minor issue. The main thing is where the production facilities are located. And today they are almost all over Ukraine. There are 18 plants in total. And they all manufacture products under our Ridne brand. That is why we came up with the idea to unite into a humanitarian consortium.

This helps a lot in communicating with international organisations. It makes it much easier to engage more humanitarian foundations in cooperation. Despite the fact that our consortium is an informal association.

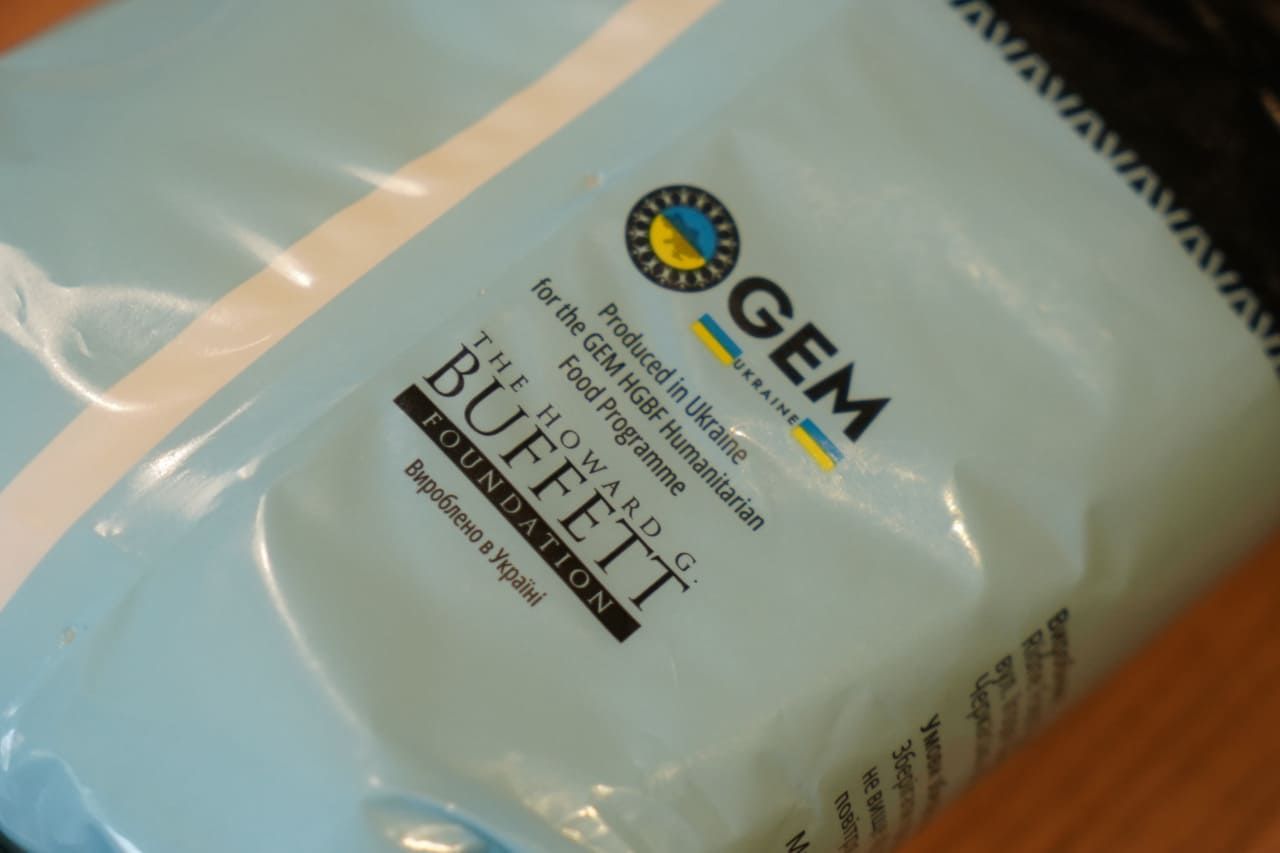

That's how we started working with GEM in partnership with The Howard G. Buffett Foundation. Today, they are implementing one of the largest humanitarian programmes in Ukraine, including food aid.

Latifundist.com: What is the company's share in the Ridne brand's total volume?

Serhiy Kovalchuk: Perhaps 15%. Which means huge volumes and a lot of cooperation and coordination. For example, several plants produce pasta alone for GEM. In particular, in Mykolaiv, Dnipro, Kharkiv and Kyiv region.

It is the same for other products. We source peas for our brand from Skvyra, Cherkasy, Kharkiv, and deliver and pack them. Canned peas come from Zolotonosha and Kolomyia. Canned meat — from Chernihiv, Bila Tserkva and Rivne. Sardines are from Cherkasy. In fact, if you look at the map, these are eight regions of Ukraine. And there are even more cities.

Latifundist.com: There have been scandals in Ukraine related to humanitarian aid ending up in shops and food markets. Does this affect your reputation in the eyes of international partners?

Serhiy Kovalchuk: Foreign foundations are very pleased with our partnership because it is based more on traditional paper documents than on any digital formats.

There are no barcodes on the products packaged under the Ridne brand. Only pasta products have them. This helps to position our products as purely humanitarian aid. It is not sold in any retail chain. In fact, TM Ridne appeared as a response to a global challenge in wartime. Our international partners are impressed by this. Furthermore, we offer special packaging with the funds' logos on it.

Three in one: business, incentive, aid

Latifundist.com: And yet, which is the core of your activities: business or charity?

Serhiy Kovalchuk: To call a spade a spade, the production of humanitarian food parcels is a business like any other. Both for us and our partners, we make money on our products and services. The only difference is that this activity is financed by international humanitarian funds.

However, there are two important aspects here. Firstly, there is a significant social component to this business. And not only because our food kits help people survive during the war. Social adaptation is equally important. The majority of the employees we hire today are IDPs: Ukrainian villages are now filled with refugees, and there are many qualified specialists among them. For example, you can talk to the head of a united territorial community, put out a call, and the next day, 3 times as many people come as needed. So, this is a particularly sensitive and urgent issue.

And secondly, cooperation with international funds is now a great incentive for agribusinesses — both in terms of self-organisation and stability. It is quite a challenge to work with food chains today as they insist on their own terms. While we have defined plans and volumes. All you have to do is start working.

Latifundist.com: Is the work on food kits a self-sufficient activity today?

Serhiy Kovalchuk: In fact, the consortium has already been formed. Although, of course, we are developing and modernising it.

In terms of quality and capacity, for instance, we have ordered new equipment for our plant in Buky and plan to install another packaging line. As for the expansion of the product range, all positions have already been covered.

Doors open to all, prospects for the brave

Latifundist.com: Which agricultural producers can become a member of the consortium?

Serhiy Kovalchuk: This is based on two factors. First, the current needs for specific products. And secondly, the willingness to work in a strict and intensive mode. In the beginning, we were struggling with many of our partners in this regard, in fact, we talked in high tones every day because of their catastrophic slackness. International foundations are not used to such relationships, they have a strict schedule.

Although today such problems rarely arise, even in the face of war-related force majeure.

Latifundist.com: Any war comes to an end. Have you already thought about what you will do when the attention of humanitarian funds to Ukraine moves to another plane, peaceful life? After the war, do you see any prospects, for instance, in processing?

Serhiy Kovalchuk: We do have such ambitions and plans to develop both processing and logistics. In fact, we are already working in the logistics and packaging hub format at our plants in Buky and Ivanky, as cooperation with international funds is built in different ways. Some of them ask us to supply ready-made food packages. Others just want packaged products from which they can make their own sets.

But in any case, this is a familiar and promising business for us. We are even now calculating the demand for innovative products, such as canned food based on American recipes in post-war Ukraine.

The global aim is to combine domestic processing of agricultural products, exports and further cooperation with international humanitarian funds into one whole. Of course, these are long-term visions, but I am confident that they can be put into life.

As a consortium, we are also uniting to effectively enter international markets, in particular, where the Ukrainian diaspora is large, and we pay special attention to African countries. We are planning consolidated participation in international food exhibitions.

Kostiantyn Tkachenko, Valentyn Khoroshun, Latifundist.com