New corn order: U.S. expands as Ukraine retreats — ASAP Agri

The February USDA WASDE (World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates) report did not dramatically alter the global corn balance sheet. What it did reveal, however, is more consequential: a clear shift in the balance of power among major exporters, marks Victoria Blazhko, Head of Editorial, Content and Analytics at ASAP Agri.

The U.S. export forecast was raised to 83.8 MMT — a new all-time record and more than 10 MMT above last year’s level. Ukraine’s forecast, by contrast, was reduced to 22 MMT. On paper, that is still 2 MMT higher y/y. But against the backdrop of the U.S. surge, the figure carries a different weight.

The U.S. is not merely harvesting a record crop — it is successfully commercializing it. Expanding into new destinations, reinforcing its presence in traditional markets, and steadily crowding out competitors. And few countries are feeling that pressure more acutely than Ukraine.

Where export interests collide

A closer look at the global corn export map reveals a clear divide: in some regions, the U.S. and Ukraine barely overlap — in others, they compete head-to-head.

South and Central America, along with parts of Asia, have long been U.S.-dominated territories. Ukraine has rarely played a meaningful role there, aside from China and occasional shipments to Japan and South Korea.

The true collision point is the European Union — a top-five importer for both exporters. And it is here that the shift in momentum is most visible.

Between 2023/24 and 2024/25, on markets of direct competition, U.S. corn exports rose by 6.5 MMT, while Ukraine’s shipments declined by 7.5 MMT.

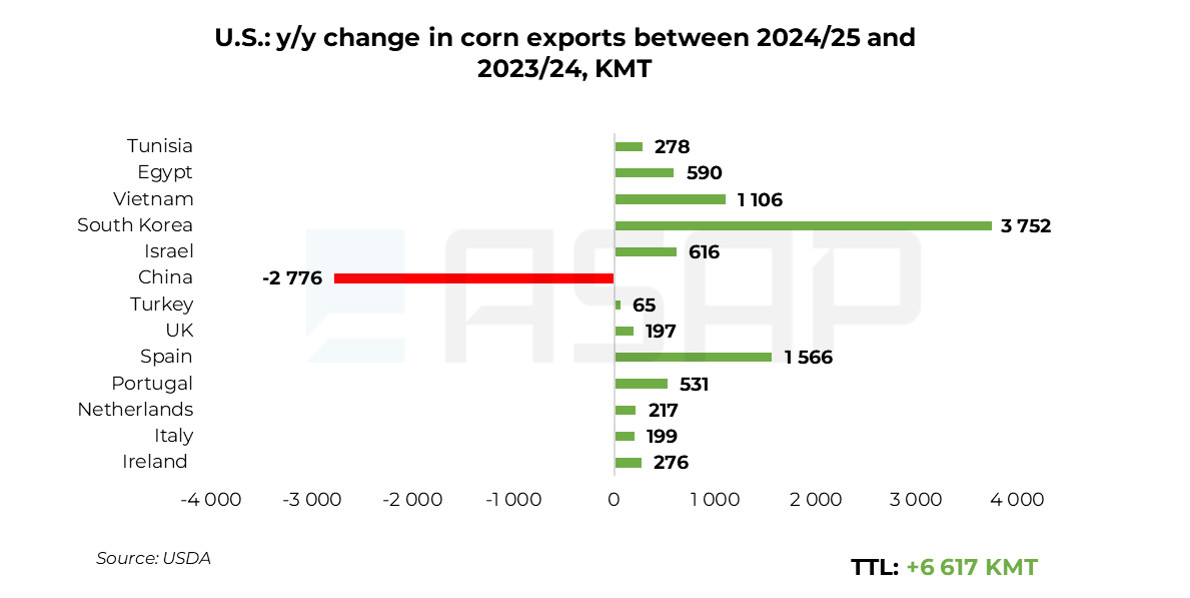

The bulk of U.S. export growth went to South Korea and the EU — particularly Spain — as well as to markets where American corn previously had limited presence, including Egypt, Tunisia, Israel, and Vietnam.

Ukraine’s export pattern looks almost like a reflection of the U.S. expansion.

On most markets where American corn gained ground, Ukrainian shipments declined. The losses were most pronounced in the EU — especially Italy, the Netherlands, and Portugal. Even a significant increase in exports to Turkey failed to offset the drop in Europe.

Turkey became the primary destination for redirected Ukrainian volumes. Beyond that, Ukraine managed to maintain or slightly strengthen its position only in a handful of markets — Spain, South Korea, Vietnam, and Israel.

China stands apart. Both exporters lost volumes there due to weaker overall imports and Brazil’s growing dominance.

Looking at September–January 2025/26 versus the same period a year earlier, the pattern is not only persisting — it is intensifying. The U.S. added another 4.8 MMT y/y. The largest increases once again came from South Korea (nearly +2 MMT) and Spain (+1.26 MMT). Additional gains are visible in Vietnam, Portugal, and Israel, with sustained volumes in Egypt.

Ukraine, by contrast, reduced exports by 1.3 MMT over the same period. Losses were again concentrated in the EU — particularly Spain and the Netherlands — as well as in Egypt and South Korea. Increased shipments to Turkey, Italy, and Tunisia were insufficient to offset the broader decline.

Last season’s contraction could largely be explained by crop size and price competitiveness. This season, the dynamics are more structural. Price still matters — often determining short-term purchasing decisions. But another, more strategic factor is emerging: sustained U.S. consolidation across key import markets.

American corn did not just enter these destinations last season — it is strengthening its position for the second consecutive year. Nowhere is this more evident than in the EU, historically one of Ukraine’s core export strongholds.

Not just price: architecture of trade

In 2025–2026, the U.S. did not rely on price alone. It reinforced its export position through structured trade agreements that lock in access and demand.

In July 2025, Japan committed to purchasing 8 BLN USD annually in U.S. agricultural products, including corn and bioethanol. South Korea, under a renewed trade framework, more than doubled its corn purchases.

In Southeast Asia, the U.S. secured duty-free access for corn, ethanol, and DDGS in Indonesia. Framework agreements with Vietnam, Thailand, and the Philippines include direct procurement of corn and corn-based products. Additional arrangements with Bangladesh and Taiwan specify concrete purchase volumes.

The European Union represents another strategic pillar. A July 2025 U.S.–EU framework agreement on “balanced trade” removed several non-tariff barriers in agriculture. While corn is not explicitly highlighted, broader liberalization creates more favorable conditions for U.S. supplies — particularly in bioethanol and feed segments. A parallel effect stems from the U.S.–UK trade agreement.

In other words, part of the recent U.S. export expansion is anchored not only in price competitiveness, but in institutionalized, contract-backed market access.

That is what makes the shift structural — not merely seasonal.

Today, Turkey stands out as the only major market where Ukraine is still expanding corn exports while facing minimal direct competition from the United States. The key factor is neither logistics nor price — it is regulation.

As of late 2025, Turkey has approved 36 GE traits — genetically engineered events permitted in imported corn and soy. The list has not expanded due to political and regulatory constraints. Every shipment is subject to mandatory laboratory testing, and the detection of any unapproved trait results in automatic rejection.

In theory, Turkey can import U.S. corn provided it does not contain unapproved genetically engineered events. In practice, however, the United States is largely absent from this market. The reason lies in the high probability that U.S. corn contains GE traits not included in Turkey’s approved list, as well as the risk of cross-contamination among different hybrids within the supply chain.

Today, around 75% of Turkey’s corn imports are supplied by Ukraine. That is why the Turkish market remains a key pillar for Ukrainian corn exports, and the future dynamics of shipments will largely depend on demand from this country.