— THN was aggressively entering the market. They included rebates in their prices, which were impossible to get.

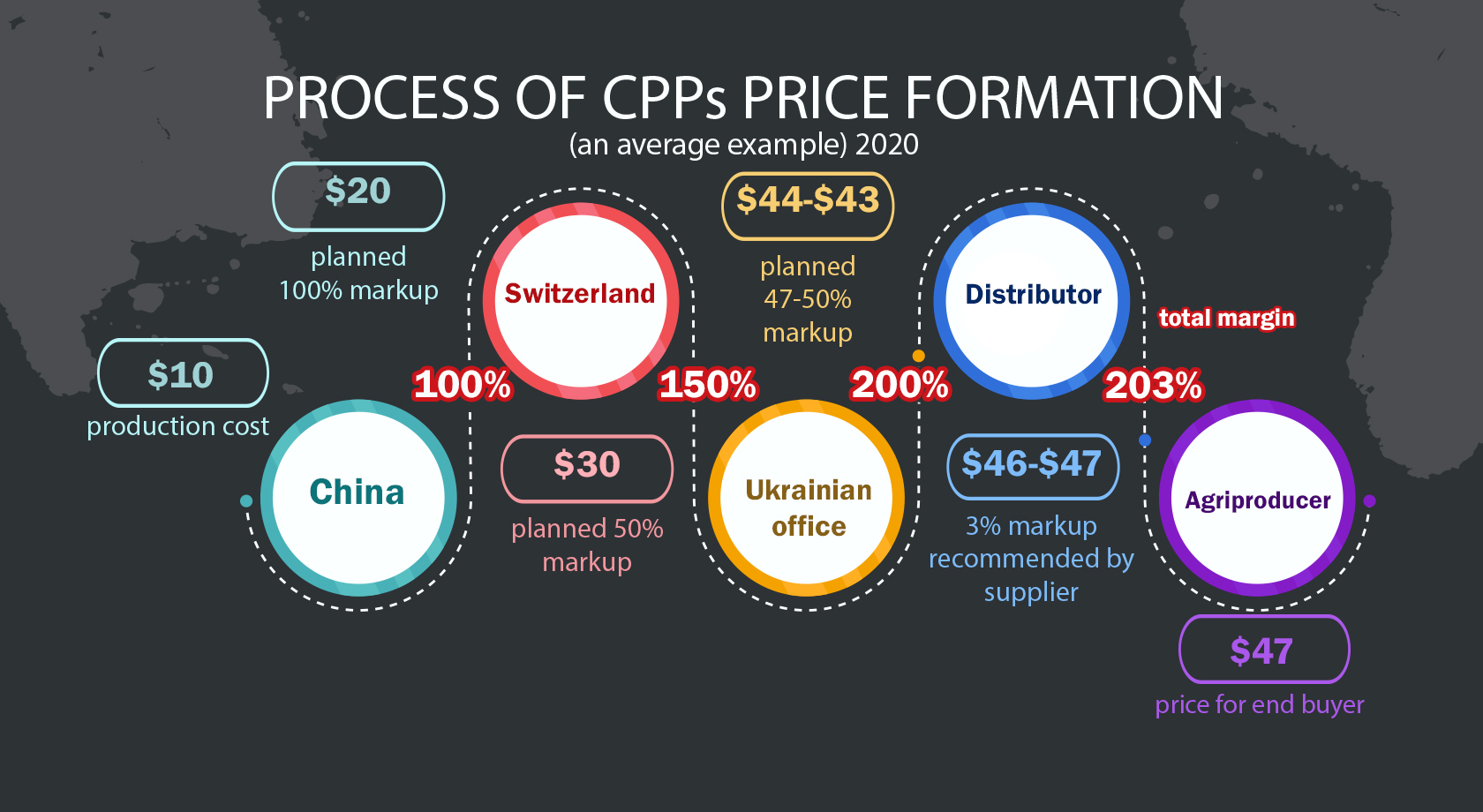

No one's ever done that before. You had a 12% prepayment discount, that was it. You included it in your price list. How do you draw a model? You take the supplier's price, you put your markup on it. If you talk to the middle management of an agricultural company, you put a 20% markup, if you talk to the director, you put a 10% markup.

And THN included all the rebates in the price from the supplier right away and built its sales from there. But eventually, there was a gap.

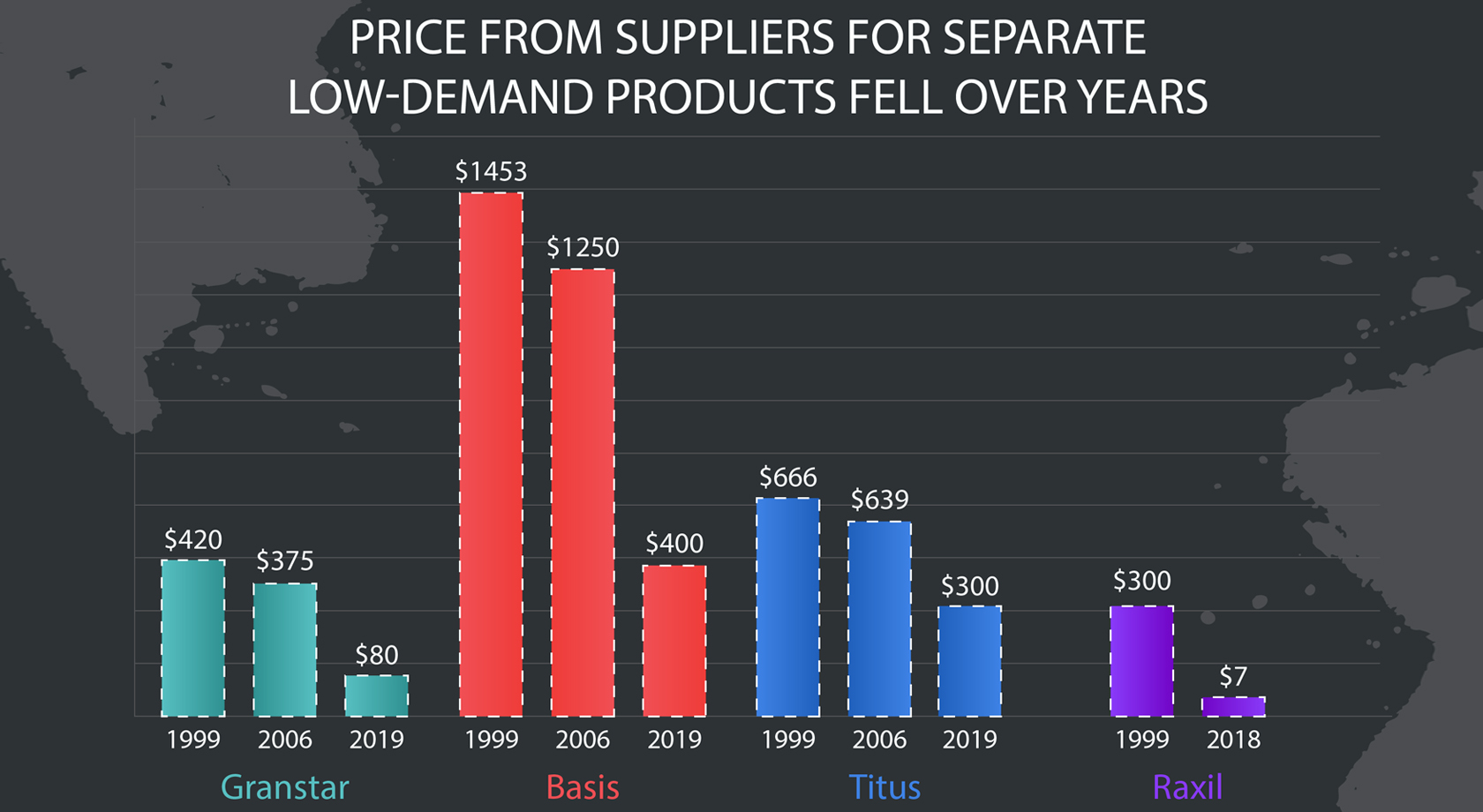

One gets rebates if he meets all the requirements: pay, ship on time. Moreover, there are certain products that you have to buy more to get a discount for the entire contract. Well, there are Corteva's

Tanos, Acanto Plus, and some other hard to sell illiquids,

DuPont's

Venzar. All companies have such products. There's an extra discount for that.

If one observes the shipping schedule, he adds another 2% to a discount.

And so THN held its head high with BASF, Syngenta, stating that it would do everything on time, collect all the goods, ship on credit to reach those maximum rebates. And what killed them was that they weren't actually selling.